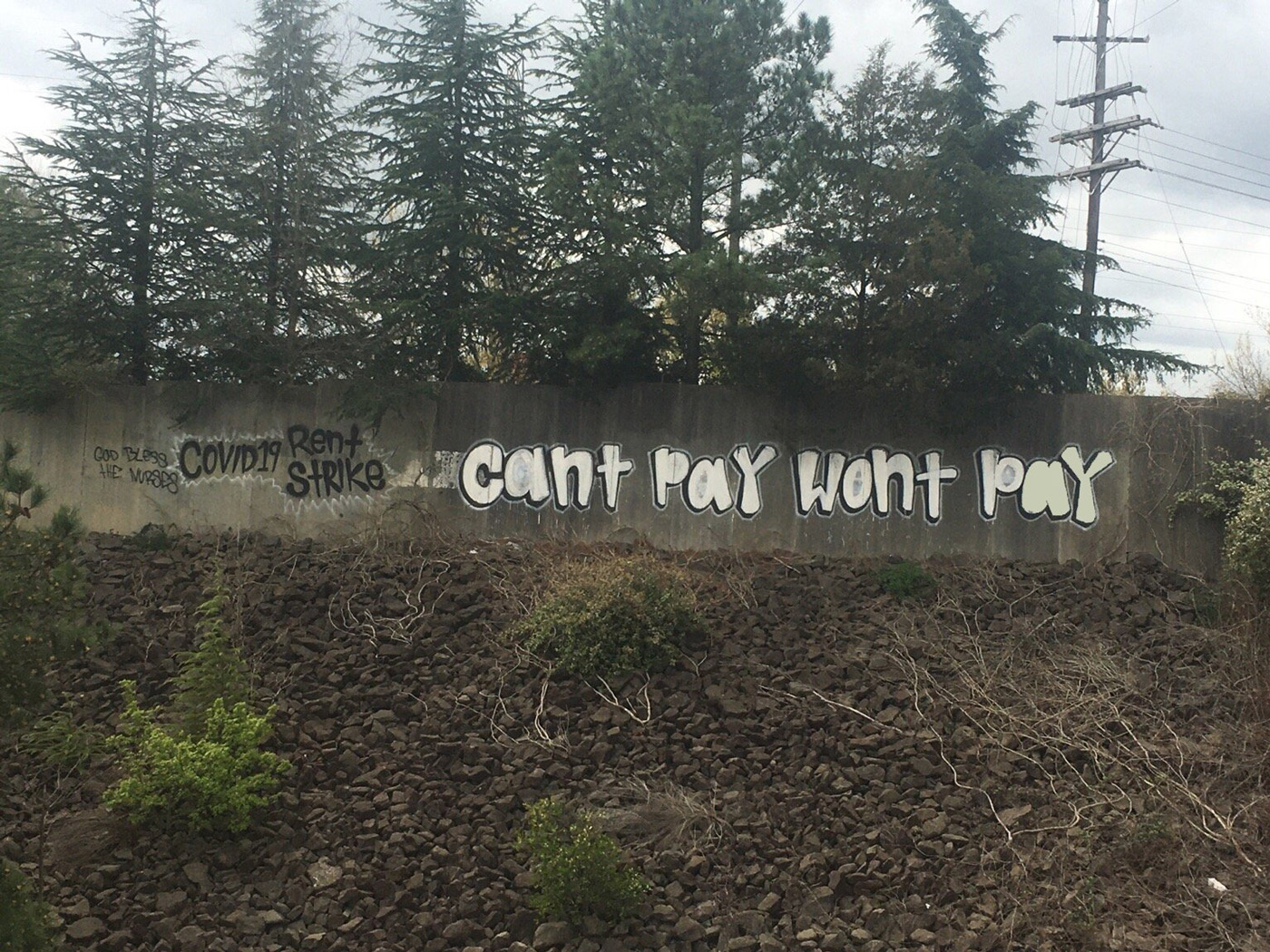

Around the world, calls are circulating for rent strikes in response to the economic hardships inflicted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the past decade, real estate values have skyrocketed and gentrification has destroyed countless communities. Housing costs were already unsustainable long before the pandemic forced the issue.

Yet how could we go on a rent strike against the economy itself? When we think of rent strikes, we usually think of a model targeting a particular landlord, advancing particular demands. In fact, as the following text documents, this strategy has been employed effectively on a much broader basis before. In a crisis in which massive numbers of people will not be able to afford to pay their bills whether or not they wish to, the important thing is to develop networks that can defend everyone who can’t pay. Over the coming months, we will have to build the capacity to confront every landlord who attempts to penalize or evict residents.

The following text is adapted from a Spanish version by Editorial Segadores and Col·lectiu Bauma, which appeared in Catalunya earlier this week. The authors review over a century of rent strikes around the world in hopes of identifying what makes them succeed or fail, in order to evaluate whether this is an opportune moment for a global rent strike.

https://twitter.com/crimethinc/status/1243930183280852992

Is This the Time for a Rent Strike?

“The fact that there are a bunch of people suddenly interested in a #rentstrike who have no experience with orthodox organizing isn’t a mark of spontaneism or ultraleftism or some moral failure to have been previously involved in orthodox organizing. It’s a mark of the fact that shifting material conditions have presented that strategy as one that combines a) survival & b) newly increased leverage. New conditions mean new modes of organization rather than stamping your foot and insisting on the old kind.”

-Joshua Clover

“But I can’t possibly evict all of them at once!”

-Apparently, a landlord seeking advice via an online forum after receiving letters from each of the 32 tenants in “his” building declaring their intention to rent strike. March 25th, 2020, Houston, TX

Station 40, a housing collective in San Francisco, is already on rent strike as we publish this.

These are strange times. Spring has arrived, accompanied by a pandemic caused by a virus that has advanced with alarming speed and the totalitarian response from the state that puts us in a new situation. While the police enjoy their new powers, many people have lost their jobs and many more already have no idea how they are going to make it to the end of the month. In this context, disobedient voices are emerging and the idea of a rent strike has gained traction. We at Editorial Segadores and Col·lectiu Bauma have wanted to investigate this kind of strike, reviewing some famous past examples and imagining what a rent strike might look like in the coronavirus era. We hope that these reflections help whoever is interested in strategizing and acting. In response to confinement—critical thought and direct action.

What Is a Rent Strike and How Does It Work?

A rent strike is when a group of renters decide collectively to stop paying rent. They might have the same landlord or live in the same neighborhood. This might occur within another campaign or as part of a bigger struggle, or it might be the principle axis of a struggle against gentrification, against insufferable living conditions, against poverty in general, against capitalism itself.

To succeed, a rent strike requires three elements:

-

Shared dissatisfaction. At the beginning, even if neighbors haven’t collectivized their demands, it’s necessary that many of them perceive the situation in more or less the same way: that it is outrageous or intolerable, that they run the risk of losing access to their housing, and that they don’t trust the established channels to provide justice.

-

Outreach. As we’ll see below, the vast majority of rent strikes begin with a relatively small group of people and grow from there. Therefore, they need the means to spread their call to action, communicate their complaints, and ask for support and solidarity. In many cases, strikers can win with only a third of the renters of a property participating in a rent strike, but sufficient outreach is necessary to get to these numbers and to make the threat that the strike will spread convincing.

-

Support. Those who go on strike need support. They need legal support for court procedures, housing support for those who lose their homes, physical support to fight evictions, and strategic support to face repression on a larger scale. In many cases, especially in large strikes, striking renters have found all the support they require within their own ranks, supporting one another and creating the necessary structures to survive. In other cases, strikers have turned to existing organizations for support. But the initiative for the strike always comes from the renters who dare to start it.

Historic Strikes and Their Common Characteristics

Now we’ll look at how these three vital elements were achieved in major rent strikes throughout history.

De Freyne Estate, Roscommon, Ireland, 1901

In 1901, a rent strike broke out on the farms belonging to Baron De Freyne, a big-time landlord in Roscommon County, Ireland. Over the preceding decades, renters in the region had consolidated their organizing power against the owners of large estates, in a movement connected to the resistance against English colonialism and the effects of the Great Famine. These movements hadn’t taken root in Roscommon, but surely the inhabitants knew of the practice and had also participated in some of the semi-illegal forms of resistance that have always been a part of rural tenancy (mass meetings, physically resisting eviction, sabotage, arson).

At the beginning of the 20th century, the residents were organized under the United Irish League, a nationalist organization that dealt with agrarian and economic issues. When the inhabitants started their autonomous strike, they quickly connected with the local UIL, while other groups connected with them to support their strike. At the same time, the high-ranking leadership acted ambiguously, sometimes offering support, other times trying to frame the strike as an independent undertaking that did not reject the concepts of rental and property outright, since the leadership of the UIL were still trying to persuade some part of the owning class to join them.

The immediate causes of the strike included a torrential rain that destroyed much of the harvest and drove up the price of feed; De Freyne’s refusal to lower the cost of rent; the accumulation of debt and the evictions of many families; and a long history of injustice with respect to land ownership, aggravated by a recent episode in which some of the inhabitants of a neighboring estate had been allowed to buy land while all of De Freyne’s tenants were forced to keep living like serfs.

The strike got underway in November 1901. At first, many of De Freyne’s tenants organized themselves clandestinely and informally, since the UIL didn’t take the initiative, although it did support the tenants. The strike spread to other estates, lasting over a year. Over 90% of the tenants on De Freyne’s lands participated. They resisted evictions by building barricades, throwing rocks at the police, and illegally constructing new dwellings.

All this caused a national scandal. In 1903, the English Parliament was forced to adopt extensive agrarian reform, putting an end to the system of tenant farming.

- Daphne Dyer Wolf, “Two Windows: The Tenants of the De Freyne Rent Strike 1901-1903” (doctoral thesis). Drew University, 2019.

The Brooms Strike, Buenos Aires and Rosario, 1907

In August of 1907, the Municipality of Buenos Aires decreed a tax increase for the next year. Right away, landlords started raising rent. The conditions in poor areas were already miserable. In the prior year, the Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation (FORA) had campaigned for the lowering of rent.

On September 13, the women in 137 apartments on one block initiated a spontaneous strike. They drove out the lawyers, officials, judges, and police who tried to eject the tenants. By the end of the month, more than 100,000 renters were participating in a strike led by women who organized in committees, aided by mobilizations and structures organized by the FORA. They demanded a 30% reduction in rent; when the police came to evict a tenant, they fought with all they had, throwing projectiles and fighting hand to hand.

The strike spread to other cities, including Rosario and Baía Blanca, drawing the support of various labor, anarchist, and socialist organizations, chief of which was the FORA. Police repression was intense; in one case, they murdered a young anarchist. In the end, although the strikers stopped many evictions, they did not succeed in forcing the landlords to reduce the cost of rent. After three months of fierce battles and the deportation of many organizers (like Virginia Bolten) under the Law of Residence, the struggle ran out of steam.

Manhattan Rent Strike, New York, 1907

Between 1905 and 1907, rents in New York City rose 33%. The city grew without stopping, swelling with poor immigrants who came to work in the factories, in construction, and at the port. There was also a surge of anarchist and socialist activity. In the fall, landlords announced another rise in rents. In response, Pauline Newman, a 20-year-old worker, Jewish immigrant, and socialist, took the initiative, convincing 400 other young women workers to support the call for a rent strike. Already, by the end of December, they had convinced thousands of families; in the new year, 10,000 families stopped paying, demanding a 18-20% rent reduction. Within a few weeks, some 2000 families saw their rent reduced. This event was the beginning of a few years of neighborhood struggle and eventual state control over rent.

Mrs. Barbour’s Army, Glasgow, 1915

In the years preceding 1915, the Scottish city of Glasgow grew rapidly with wartime industrialization and the immigration of rural families. The property-owning class speculated on housing, leaving 11% of houses vacant and not financing new construction, while the working class found themselves in ever more crowded and deteriorating homes. Organizations such as the Scottish Housing Council and various labor unions spent years working to execute legal reforms in the housing and renting sector; they won some new laws, but in general, the situation continued to worsen. Furthermore, with the Great War, the prices of food rose without stopping and many of the country’s men were abroad. The property owners took advantage, thinking that it would be easier to exploit poor families with their men gone. From August to September 1913, there were 484 evictions in Glasgow. From January to March 1915, there were 6441.

In the misery, exploitation, and carnage that persecuted the working class, the property owners of Glasgow saw a good opportunity. In February 1915, they announced a 25% price increase for all rentals. Immediately, on February 16, all of the poor women in the southern part of the Govan neighborhood held a mass meeting. In attendance were the organizers of Glasgow Women’s Housing Association, an organization that had formed the previous year but still had little traction. At the meeting, they created the South Govan Women’s Housing Association, affiliated with GWHA. They decided not to pay the increase, but instead to continue paying the original rate. This spread throughout the neighborhood.

GWHA called a rally for May 1, drawing 20,000 participants. In June, the women of Govan won the cancellation of the rent increase. The movement grew from there. In October, more than 30,000 people participated in the rent strike all over the city. They came to be known as Mrs. Barbour’s Army, named after Mary Barbour, a worker of Govan. In the course of spreading and maintaining the strike, they organized rallies and protests and defended tenants against evictions, fighting hand to hand with the police. The unions threatened to go on strike in the armament factories; at the end of the year, they succeeded in winning the suspension of any punitive action against strikers, a rent freeze maintaining pre-war rent prices, and the first rent control laws in the United Kingdom—an important step towards social housing, which was introduced not long after.

From early on, the movement won the support of leftist parties and other existing organizations that focused on housing, like the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations, connected with the Socialist Party. But it’s important to highlight that the women created autonomous organizations rather than joining traditional organizations. Some, like Mary Burns Laird, the first president of GWHA, also organized with political parties (the Labor party, in the case of Laird), while others, like Mrs. Barbour, weren’t affiliated with any party, creating their own path for the struggle. In any case, the GWHA’s activity was far from traditional leftist politics: their meetings took place in their kitchens, in washhouses, and in the streets. In large part, the force behind the acronym was the solidarity network that the poor women had already established in their daily caretaking activities.

-

Brenda Grant, “A Woman’s Fight: The Glasgow Rent Strike 1915,” 2018

Comité de Defensa Económica, Barcelona, 1931

In 1931, Barcelona had recently emerged from dictatorship. People eagerly awaited the improvements that democracy would bring… and they kept waiting. Barcelona had become the most expensive city in Europe, with rent amounting to 30%-40% of wages. (Today’s figures are similar, or even worse, but at the time, the average in European cities was 15%.) Conditions were abysmal. Many who could not afford to rent a place for themselves went to the “Casas de Dormir,” rooms where they could rest between factory shifts; often, these rooms didn’t even have beds, just ropes on which workers could rest their arms.

A rent strike erupted in April with the participants demanding a 40% reduction in rent. It lasted until December, involving between 45,000 and 100,000 people throughout the city. The Comité de Defensa Económica (CDE), or Economic Defense Committee, founded by the construction union of the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, National Confederation of Workers), played a crucial role in the coordination and spread of the strike.

Like so many other strikes, this one was characterized by solidarity among striking neighbors who built barricades and resisted evictions together. When they succeeded, they celebrated in the street; when they did not, they broke back into the evicted house and celebrated inside. The very same workers who shut off the water or electricity in the morning came back in the evening to turn it back on. They were, of course, afiliated with the CNT. Sometimes the police ended up throwing furniture out of the windows or otherwise destroying it, fed up with having to return to reoccupied homes. Other tactics included what is known today as escrache, that is, protests in front of a landlord’s house.

Obviously, the strike didn’t come out of nowhere: it was based in community traditions of autonomy and rooted in a multifaceted network of relationships and ties that grew out of neighborhood and kinship. The movement was also closely linked to the radical culture that the CNT had been fostering since World War One.

“Santiago Bilbao, organizer of the CDE, saw the tenants’ strike as an important act of economic mutual aid through which the dispossessed could counteract the power of the market and take control of their daily lives. The CDE’s advice to the workers was: “Eat well and if you don’t have money, don’t pay rent!” The CDE also demanded that the unemployed be exempt from paying rent. However, although the strike spread through mass meetings organized by the CDE, the movement really came from the streets, which were more essential to it than any organization.”

“The rent strike was born in the neighborhood of Barceloneta where there is a vital social consciousness, both from the hard lives of fishermen and from the laborers who work in the Maquinista Terrestre y Marítima, one of the most important companies in the metal industry. It’s no surprise that these grievances emerged from this historic fishing neighborhood next to the Mediterranean, where fishermen’s houses are still known as matchboxes. These were homes of 15 or 20 square meters where whole families lived, sometimes with lodgers such as relatives recently arrived from the village. […] It is the Sindicato Único de la Construcción of the CNT that will mobilize the discontent of working families, which, little by little, will spread to the margins of the city and in each of those neighborhoods, the strike will have its own characteristics, its own idiosyncrasies and methods of struggle.”

-Aisa Pàmpols, Manel, (2014) “La huelga de alquileres y el comité de defensa económica,” Barcelona, abril-diciembre de 1931. Sindicato de la Construcción de la CNT. Barcelona: El Lokal.

The strike was effectively ended by means of severe repression, headed by governor Oriol Anguera de Sojo and the president of the Property Owners Association, Joan Pich i Son, who also killed the insurrection of October 1934. The new democratic republic did not look much different from the old dictatorship once it brought out its entire arsenal: police, Guardia Civil (Civil Guard), and the Guardia de Asalto, the new paramilitary police. The Law of the Defense of the Republic was applied, a gag law that offered carte blanche for repression. Some were imprisoned as “governmental prisoners” and the CDE was declared a criminal organization.

Despite all this, the continued protests continued to stoke the embers for the revolution that was to come.

Much of the original documentation of the strike was destroyed in the war, perhaps as a result of the fear inspired by this example of proletarian resistance. Consequently, we are missing a large portion of the voices of the women who played a central role in the strike. Formal organizations are always given more weight in historiography than informal organizational spaces, although there is no doubt that the central role of the CNT was an important feature of the strike. However, the fact that strike tactics were different in each neighborhood tells us that the strike was not centralized, but depended above all on the initiative of those who carried it out.

-

Aisa Pàmpols, Manel, (2014) “La huelga de alquileres y el comité de defensa económica,” Barcelona, abril-diciembre de 1931. Sindicato de la Construcción de la CNT. Barcelona: El Lokal.

St. Pancras, London, 1959-1960

St. Pancras, in London, was a mostly working-class area, with some 8000 people living in social housing.

In 1958, the district voted to raise the rent in social housing. At the end of the following July, after the Conservative Party won the district elections, they raised rents again, this time more dramatically (between 100% and 200%), and kicked out the unions (whereas previously, workers in the district had to be members). Up to that point, there had been little neighborhood organization, but as August began, tenants in one district neighborhood formed an association. By the end of August, 25 such tenant associations had been formed and these had representatives in the central committee of a new organization, the United Tenants Association. The secretary, Don Cook, had already been secretary of one of the few (and small) tenant associations that existed before 1959.

From the beginning, most of the base favored direct action and a rent strike, but the Labor Party, which wanted to use the tenants’ demands to beat the Conservative Party and regain control in the district, held them back.

On September 1, 1959, a march and meeting took place involving 4000 people. The participants adopted positions including a refusal to fill out the required paperwork to evaluate each family’s new rent, a call for unity, a promise to defend any family facing eviction, and a demand for solidarity from the unions. Over the following months, the tenants continued to hold demonstrations and, with support from the unions, established committees on every block, which held weekly delegate assemblies often attended by 200 or more participants. They published three weekly newsletters to disseminate information from the leadership to the base. By the end of the year, the UTA included 35 tenant associations.

Women protested by night at the homes of district counselors. Each counselor was targeted twice a week or more. They lost plenty of sleep. One of the few stories of the strike written by a participant (one Dave Burn) recognizes that women “formed the backbone of the movement, remaining active every day and supporting each other.” Still, most of Burn’s story focuses on formal, predominantly male delegate organizations.

The rent hike was set to take effect on January 4, 1960. At first, fully 80% of social housing tenants didn’t pay the increase, only the previous rent. After many threats and with the district’s eviction process beginning, participation in the strike dropped to a quarter of all tenants, or about 2000. In February, the Labor Party advised the UTA to call off the strike so they could negotiate with the Conservatives. The UTA refused: without the strike, they would be totally defenseless and several families were already in the midst of eviction processes.

To concentrate their forces, the UTA organized a collective payment of most of the back rent so they didn’t have to fight so many evictions at once. The first judgments were issued and three evictions were scheduled for late August. Tenants began to organize their defense, determined not to allow a single eviction from social housing. In the middle of that campaign, in July, UTA leaders met with district counselors—but the negotiations failed, since the Conservatives didn’t want to hear anything about tenants’ problems. From that moment, the UTA began a total rent strike, and in mid-August, 250 more eviction notices arrived.

By August 28, massive barricades had been erected; tenants had prepared a system of pickets and alarms to alert the entire neighborhood, so that workers could walk out and come to defend people’s homes. As of August 14, the number of eviction notices had risen to 514. The Labor Party and the Communist Party feared the rising tension and called for the strike to end, but it was too late.

On the morning of September 22, 800 cops attacked. A two-hour battle followed in which one policeman was seriously injured. Police managed to evict two homes, but on one block, the clashes continued until noon. Some 300 local workers came to help defend the strike—but the labor unions did not offer support. In the afternoon, a thousand cops attacked a march of 14,000 tenants. Confrontations continued.

The leader of the district counsel signaled that he was prepared to meet with UTA representatives. The next day, the Minister of the Interior declared the prohibition of all demonstrations and gatherings.

Due to the political scandal the riots had caused, the Labor Party abandoned the tenants and began to denounce “agitators” and “radicals.” They alleged the involvement of outside provocateurs and insisted that the conflict had to be resolved through dialogue—despite the fact that throughout the year, the district’s Conservatives had nearly always refused dialogue. Meanwhile, after negotiations, the Conservatives approved a small rent reduction.

Under attack as much from the left as from the right and facing daily threats of new evictions, the UTA decided to change strategies to avoid more evictions. They paid the back rent due from neighbors who faced the highest risk of eviction and decided to aid the Labor Party to oust the Conservatives in the coming elections. In May 1961, the Labor Party won control of the district counsel, 51 counselors to 19. Several UTA delegates had joined their ranks and the main plank of their electoral platform was rent reform.

Tenants awaited the reform of the rental plan in social housing… and waited… and waited. The two tenants who had been evicted found new homes, but after a few months, Labor counselors announced that rent reform would not be possible. The strike had failed.

Autoriduzione, Italy, 1970s

The 1960s and ’70s in Italy were a time of increasing precarity in labor and housing, and also a moment in which people dreamed of a world without exploitation and dared to pursue it. In 1974, counting on the neutrality of the Communist Party, the most forward-thinking technocrats of the industrial and financial sectors introduced Plan Carli. This Plan aimed to increase labor exploitation and reduce public spending.

During the 1960s, a strong autonomous workers movement in Italy had influenced the rise of an autonomous movement in the neighborhoods based in self-organized neighborhood committees in which women played a crucial role. Focused on practical and immediate survival, these committees organized “auto-reductions” in which tenants and neighbors themselves decided to reduce the price of services—for example, only paying 50% for water or electricity.

In Torino, the movement gained considerable momentum in summer 1974. When public transit companies decided to raise fares, the response was immediate. Participants spontaneously blocked buses at various points, distributed pamphlets, and sent delegates into town. From there, the most militant unions began to organize a popular response: they would print transit tickets themselves and volunteers would hand them out on buses, charging the previous price. Through collective strength, they forced the companies to accept the situation.

The auto-reductions in electricity payments spread quickly, organized in two phases: first, collecting signatures committing to participation in the auto-reduction, in both factories and neighborhoods; second, picket lines outside the post office, taking advantage of leaked information from the public utility unions about when and where bills were mailed. Picketers handed out information about how to participate in the auto-reduction. After a few weeks, 150,000 families in Torino and the Piedmont region were participating.

Auto-reductions were stronger in Torino because the regional unions were autonomous from the national committees controlled by the Communist Party, which blocked every direct action initiative against rising prices. Thus, in Torino, the labor unions could lend their power and support to spontaneous initiatives and those by neighborhood committees, while in cities such as Milan, the unions did not support those initiatives or else, as in Napoli, there were no strong unions in the first place. In some cities, like Palermo, students and young people made auto-reductions possible through illegal actions.

The movement extended to auto-reductions in rent, aiming to keep rent from exceeding 10% of a family’s salary. Various tactics were employed from small group efforts to neighborhood committee initiatives backed by the more radical unions. In the first half of the 1970s, participants squatted 20,000 homes, temporarily liberating them from the commercial logic of rent. There were also rent strikes in Rome, Milan, and Torino.

The feminist movement was a major part of these efforts. In this context, women developed the theories of triple exploitation (by bosses, husbands, and the state) and reproductive labor, which remain crucial in present-day struggles.

Soweto Township, South Africa, 1980s

Soweto is an urban area of Johannesburg with a high population density. In the 1980s, it had 2.5 million inhabitants. Throughout the last decades of Apartheid, the residents of Soweto experienced extreme poverty and social exclusion. In 1976, this erupted in the Soweto Uprising, a series of powerful protests and strikes and a police crackdown that ended in dozens of deaths. The material conditions of the area began to improve, but only thanks to the continued struggle of the residents.

The housing situation was appalling. Houses were of poor quality, unhygienic, and disordered. Rent and services amounted to a third of the typical salary of the residents, not counting the skyrocketing unemployment rates. On June 1, 1986, when word spread of a plan to raise rents, thousands of Soweto residents stopped paying rent and services to the Soweto Council. The Council tried to break the strike with evictions, but the neighbors resisted with force. In late August, police shot at a crowd that was resisting an eviction, killing more than 20 people. Rage intensified and the authorities halted the evictions.

In early 1988, the authorities declared a state of emergency to try to suppress the rise of black resistance across the country. The sole focal point that they did not manage to extinguish was the Soweto rent strike. In the middle of the year, the strikes continued and the authorities cut off the electricity to nearly the entire area as a means of pressure.

The press claimed that the strike was not realistic, that it was only sustained by the violence of young militants. The reality turned out to be different: despite 30 months of a state of emergency that stopped much of the activity of the anti-apartheid movement, the vast majority of the residents continued to support the strike. In the end, the authorities recognized that they had completely lost control. In December 1989, they canceled all overdue rents—a loss of more than $ 100 million—definitively stopped evictions, suspended all rents pending negotiation with neighbors, and, in at least 50,000 cases, ceded ownership of the houses directly to the tenants.

Before these strikes, the anti-apartheid movement had used rent strikes as a tactic in its protests against the white government, so the entire population was familiar with them; the mobilizations and organizations of this movement had extended the practices of solidarity. But the first major rent strike started in September 1984 in Lekoa as an immediate response from the neighbors themselves to a rent increase; the most involved organization was the Vaal Civic Association, Vaal being the local region. This was probably the source of the rent strike tactic that the African National Congress (ANC) and other organizations subsequently began to use.

Similarly, the Soweto rent strike emerged from the neighborhood itself in response to its immediate conditions and survival imperatives. It is a classic example of informal neighborhood networks being key to the organization of strikes, with formal structures being created as needed once the strike had already begun. And while they were excluded from some of the formal organizations, women maintained a key role in organizing and maintaining those vital neighborhood networks.

-

South Africa Blacks Plan Mass Action: Store Boycotts, Rent Strikes Are Part of Strategy

-

Soweto City Council Drops Campaign To Crush Rent Boycott

Boyle Heights Mariachis, Los Angeles, 2017

In an attempt at racist gentrification, a homeowner raised rental costs by 60-80% on a small number of apartments in a building next to Mariachi Plaza in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. Half of the tenants formed a coalition immediately—including tenants not directly affected by the rent increase—and demanded dialogue with the landlord. When the landlord tried to engage with each of them separately, the coalition launched the rent strike. Subsequently, the Los Angeles Tenants Union (LATU) began supporting the strike, helping to mobilize and secure legal resources.

After nine months, they received a rent hike of only 14%, a three-year contract (very rare in the US), the cancellation of any penalty for non-payment, and the right to negotiate the next contract as a collective after three years.

Burlington United, Los Angeles, 2018

A strike began in three buildings on the same property on Burlington Avenue, a Latinx neighborhood in Los Angeles affected by rapid gentrification, at a moment when the number of homeless Latinx people had been skyrocketing. When the landlord raised tenants’ rent between 25% and 50%, 36 of the 192 apartments declared a rent strike; the poor conditions in the buildings were also one of the complaints shared by the tenants. By the second week, a total of 85 apartments were on strike, almost half. The residents organized themselves starting with the strike declaration. Subsequently, the local LATU and a nearby neighborhood legal defense activist organization opposing evictions provided assistance to the strikers.

The legal system divided resistance through separate court processes for each apartment. Half of the apartments won their judgments; the others were forced to leave.

Parkdale, Toronto, 2017-2018

In 2017, the tenants occupying 300 apartments in multiple buildings with the same owner carried out a successful strike in the Parkdale neighborhood of Toronto. The neighborhood was undergoing rapid gentrification and the real estate company in question had already earned a bad reputation among its tenants for poor apartment conditions and trying to force them out via price increases.

When the company tried to raise prices, some neighbors decided to declare a strike; others quickly joined, organizing as an assembly. Another important element in the context was the activity of Parkdale Organize, a tenants’ organization from the same neighborhood that had emerged out of another neighborhood struggle in 2015. Parkdale Organize helped mobilize the strike, knocking on doors in the affected buildings, offering resources, and sharing models of resistance. After three months, they managed to block the rent increase.

Inspired by this example, tenants in another large, 189-apartment Parkdale building began a strike the following year. When the real estate company decreed a sharp rise in rents, the tenants in 55 apartments organized in an assembly and went on strike. After two months on strike, the tenants won their demands and the owner canceled the rent increase.

-

Parkdale Tenants Stage Rent Strike to Protest Unfair Rent Hike

-

Parkdale Tenant Strike Expected to End after Landlord Backs Down on Rent Increase

Common Characteristics

Most of these strikes were started by women; women played an important role in all of them. The strikes always occur in a context in which many tenants suffer similar conditions: rent that takes up a large proportion of salaries; the danger of losing housing; and some additional cause for outrage, such as very unhealthy conditions, a contextual issue like English colonialism (as in the Roscommon strike), or an unjust reform that favors some and harms others. And there is almost always a spark: most commonly, a price increase or a decrease in the economic opportunities of the tenants.

Often, strikes began spontaneously, which does not mean they appeared out of nowhere, but that they arose—in a favorable context—from the specific initiative of neighbors, implemented through an assembly or through affective and neighborhood networks. From there, they either create their own organizations or draw the support of existing organizations. In other cases, a formal organization exists from the beginning of the strike, but it is a rather small organization created by and for tenants, not one of the big union organizations or parties. We have only found one case in which a rent strike was called for by a large organization—1931 in Barcelona.

Regarding the chances of victory, it is important for the strike to spread as widely as possible, but it isn’t necessary that it involve a majority. Strikes have been won with the participation of only a quarter or a third of the tenants under the same owner; in the case of strikes in a given territory, that are not directed against a particular owner, it may be a much smaller proportion of the total inhabitants of a city, as long as there are enough to interrupt normalcy, provoke a crisis in the government, and saturate the legal system. The determination to maintain high spirits and solidarity rather than seeking individual solutions is more important than the number of strikers.

Another factor, perhaps the most important, depends on context. What are the state’s capacities to inflict repression? Is it better for them to crush disobedience, or to appease conflict and restore their image?

Current Conditions: More than Adequate

As we have seen, certain conditions are necessary for a rent strike to spread throughout the population: precarity that makes it impossible for more and more people to access housing and a shared sense that things are going very badly. Do these conditions currently exist?

Increasingly, large international investment funds are buying up property around the world and setting rent at record highs. As they devour the housing market, the price that people have to pay for access skyrockets.

For example, in the Spanish state, the price of rental housing reached its historical apex in February 2020 (the last month for which the data was available at the time of writing this text) at €11.1 per square meter, an increase of 5.6% over February 2019. The communities with the highest prices are Madrid (€ 15.0) and Catalonia (€14.5). In Madrid City, the price is €16.3 per square meter, a growth of 3.5%; and in the city of Barcelona, €16.8 per square meter, a growth of 3.7%. But all the tourist cities have experienced a similar increase. Between 2014 and 2019, the average rental prices in the Spanish state have risen 50%, far exceeding the highest point before the 2008 crisis.

Over the same time period, the average salary in the Spanish state has not even risen 3%. That’s right: a 50% increase in housing costs and a 3% increase in salaries. But the mean salary includes both working people and millionaires, and the latter do not have to pay rent. If we refer to the median salary or the salary earned by the greatest number of people (i.e., the most common salary among the masses), we see that it has risen much less and has even decreased in some years. In short: now there are more people than ever who cannot access housing. We have seen this situation coming for the past five years, long before the coronavirus.

This lack of housing access shows in the statistics, as well. In 2018, there were more than 59,000 evictions in the Spanish state, with an increasing proportion of evictions for non-payment of rent. In 2019, there were more than 54,000, 70% via the Urban Rental Law. Both years, the communities of Catalonia and Andalusia led in the number of evictions. The decline between 2018 and 2019 is largely explained by the resistance to evictions that has emerged everywhere and by the trend towards fewer foreclosures each year, as fewer people can get mortgages now and banks are more willing to negotiate after the explosion of resistance over the last twelve years. Between 2017 and 2019, the number of homeless people in Madrid grew by 25%, officially reaching 2583 people, although other experts say that there must actually be around 3000. There are an estimated 40,000+ homeless people throughout the Spanish state. [In the United States, the number of homeless people in Los Angeles alone exceeds this.]

The coronavirus pandemic only exacerbates this situation. Many people have lost their jobs; it is no surprise that the government’s emergency measures have been more concerned with increasing police and martial powers, protecting financial institutions, businessmen, and people with mortgages, and therefore have left the most precarious people unprotected—tenants, people without papers, and the homeless. On the other hand, it is a time when solidarity initiatives have spread at the speed of light, with cacerolazos (noise demonstrations with pots and pans) on the balconies and a rapid expansion of social demands, all despite the state of siege imposed by the government.

In short, it is not just the right time for a rent strike, but there is more need than ever to organize such initiatives right now. If this is not the time—all-time highs for housing precarity, a pandemic, and the rapid spread of social initiatives—perhaps there will never be a suitable time to launch a rent strike?

Tenants’ Concerns

It is understandable that renters who might be in favor of going on strike will have a number of doubts.

Practical and Legal Concerns

Initial doubts stem, simply, from a total lack of familiarity with rent strikes: to our knowledge, there has been no rent strike in Spanish territory since 1931. How does it work? What are my rights and what are the possible penalties if I stop paying the rent?

In short, you only have to do two things to join the rent strike: stop paying and communicate it to others. You can communicate your non-payment to the owner or not do so. Communicating it may make the strike stronger, but if several tenants of the same owner join the strike, that will also convey the message. The Union of Tenants of Gran Canaria has an example of a form that you can send to the owner.

The second step is very important: informing others that you have joined the rent strike. The more people join, the less danger there is for each person. Talking to your neighbors is the best way to encourage them to join the strike. It is also very important to communicate about the strike to networks that can provide solidarity in your neighborhood. These could be neighborhood associations, housing or tenant unions, or even solidarity-based labor unions such as the CNT. If they know more or less how many people are on strike, they will be able to distribute information and resources and help organize a collective defense in the event of an eviction process. Remember: together, we are much stronger.

As for the legal consequences, if you stop paying the rent, the landlord may start an eviction process to kick you out of your apartment. But in many cases, when multiple tenants of the same landlord stop paying the rent, the landlord is compelled to reach an agreement that can include a rent reduction. In a situation of generalized crisis like the current one, it is very possible that the state will intervene with a moratorium on evictions if many people go on strike.

You can find more information about legal rights [in the Spanish state] here and here.

Emotional Concerns

The emotional aspect is essential in a rent strike. Precarious housing exists everywhere, every day. The fundamental element to spark a rent strike is the courage of those who say enough is enough, who decide to take risks, to take the initiative. It is a bit of a paradox: if everyone dares, victory is almost guaranteed and there is very little risk. But if everyone hesitates, without the safety of the group, the few who dare may lose their homes.

Yet right now, we obviously have the advantage. Millions of people from humble neighborhoods are in the same situation—and we all already know that we are in this situation. There will not be “a few” who take risks, because there are already tens of thousands who have lost their jobs and will not be able to pay their rent, and this number will only increase. If we suffer in silence, we may not risk anything, but all the same we may lose our homes. But if we raise our voices and collectivize our struggle, we have everything to gain and nothing to lose. The slightly more privileged people—those who can survive a month, two months, three months without pay, or who have retained their jobs—also have a lot to gain if they join the thousands of people who have no other way out, because none of us know how long the quarantine will last or how long the consequent economic crisis will continue. Regardless of the pandemic, in most of the cities in the Spanish state, we were already losing access to housing. If normality returns… then tourism will return along with Airbnb, gentrification, and the unbearable pressure of ever-rising rent.

We have another advantage on our side: during the state of emergency, the courts are also paralyzed. Some cities have already postponed all evictions and other municipalities will not be able to manage them at all, or only extremely slowly.

There could not be a better time to start a rent strike. The only thing that is needed is to raise our voices and collectivize the situation that we are all experiencing.

Organizations Specializing in the Housing Struggle

Social organizations play a very important role in a rent strike. They can convene it, they can support it—or they can damage it. What are the characteristics of a strong and effective relationship between the housing movement and organizations?

First, we must recognize the reality of movements for housing. The movement consists of everyone who suffers from poor housing conditions or who is in danger of losing access to housing. They, the precarious, are the ones who have everything to lose and everything to gain; they are the ones who have to take the initiative to declare a rent strike or other acts of resistance.

Organization is a matter of the utmost strategic importance within a rent strike, but there is no specific organization that is essential. An organization that is already very strong can call the strike, as in Barcelona in 1931. But if the neighbors themselves need to go on strike, they will call the strike themselves and then create the organizations they need to build support and coordinate their actions. Even when organizations specializing in housing already exist, if they do not respond to the residents’ immediate needs, the residents will ignore them and create their own organizations. And in the very unfortunate case that an organization considers itself the proprietor of the movement and tries to lead it according to its own political needs rather than the needs of the residents, as occurred in the strike in St. Pancras, London, in 1960, it will end up sabotaging the strike and harming the tenants.

The fact that the vast majority of rent strikes have been organized by women reflects this dynamic: the formal organizations of the Left have emerged largely according to a patriarchal logic that puts “party interests” ahead of the human needs of the most affected people. For this reason, women often organize their own structures, among other things, within their own networks and with their own methods, rather than joining the large organizations that already exist.

A strong and effective relationship between the housing movement and social organizations could be based on these principles:

-

Social organizations respond to the needs of the residents. They can help to formulate strategies, but they should not turn a blind eye to the realities and inclinations of the residents.

-

Organizations exist to support residents, not to lead them. If the organizations assume that their leadership is essential, residents will likely have to create their own initiatives when action is urgent.

-

The most important support structures that organizations can provide are psychosocial and defensive. In regards to the first, the organization helps residents to see that they are not alone—that together they are strong, they can win. In this sense, the essential thing is to feed people’s spirits, not to discourage them or sow fear or false prudence. As for their defensive role, this is the activity of coordinating physical resistance to evictions and gathering legal resources for legal processes. Without this activity, the strikers will fall house by house.

By contrast, what are the characteristics of a counterproductive relationship between social organizations and the housing movement?

Specialist activism. It is admirable when people dedicate their lives to solidarity struggles for dignity and freedom. But problematic dynamics arise when a specialization is derived from this approach that generates distance between the experts and “normal people.” In the case of the fight for housing, activists may end up being more aware of the perspectives of other “organized” activists and militants than they are of what is happening to other residents and precarious people. Consequently, they prioritize the interests of the organization (affiliating more members, looking good in the press, gaining status through negotiations with the authorities), when the interests of the residents should always take precedence (gaining access to decent and stable housing).

This alienation between activists and neighbors can manifest itself as false prudence. It is true that a rent strike is a very hard fight; it is not something to propose lightly. But taking a conservative position in the current situation seems to us to deny the reality that many people are already experiencing. A rent strike is dangerous—but it is undeniable that within the current crisis, the danger is already here. This month, tens of thousands of people will not be able to pay the rent, not to mention the tens of thousands who already live on the street in a situation of absolute vulnerability.

The danger of specialist activism is especially great in the case of economically privileged people. It is admirable when people from well-to-do families decide to fight side by side with precarious people. But it is totally unacceptable for such people to try to determine the priorities or set the pace of the struggles of the precarious.. As in all cases of privilege, they should be transparent with their companions and honest with themselves and support the struggles of precarious people instead of trying to lead them.

Limited scale or fragmented vision. It is entirely understandable that people who have spent a lot of time fighting for housing would feel a little overwhelmed or doubtful about a general call for a rent strike. Indeed, it would be troubling if they didn’t feel that way. It has been more or less a century since we saw rent strikes on this scale. But we must also acknowledge that it has been nearly a century since capitalism has experienced a crisis as intense as the one developing today—and the rent strike continues to be an effective tool. It should give us some peace of mind to know that tenants and organizations that have been involved in rent strikes for the past three years in Toronto and Los Angeles are supporting the current international call.

As for the danger of dividing up the struggles, we consider totally unacceptable any call-out that does not take into account the needs of the homeless and those without documents. Although it is understandable that many organizations seeking short-term changes focus on a more specialized field or topic, they should not contribute to the fragmentation of struggles, undermining the possibility of solidarity. It is a tactic of the state to offer solutions for people with mortgages but nothing for tenants. We should not reproduce this approach even if we have good intentions. Therefore, all calls should support a moratorium on evictions and also legitimize the practice of occupying empty houses, or at least connect with calls that do.

The Reform/Revolution dichotomy. To speak plainly, it’s an illusion to believe that it’s possible to win a revolution and abolish all oppressive structures from one day to the next: revolutions consist of a long path of struggle after struggle. It’s also an error to believe that it is possible to gain real reforms without creating a force that threatens the power of the state: states maintain social control and the well-being of the economy and they don’t protect those who are dispensable to those causes. Almost all really beneficial reforms have been won by revolutionary movements, not by reformist movements.

There is a lot of important debate about the appropriate relationship between the state and political movements, about tactics and strategy. But we are stronger when we work together—when those who are dedicated to small but urgent gains are connected to those who work against the fundamental sources of exploitation and fix their gaze on a horizon where exploitation no longer exists. At the end of the day, our struggles comprise an ecosystem. We’ll never convince the whole world to think like we do, nor will we dominate all social movements; whoever tries to do so only weakens their movement. We should cultivate healthy relationships based in solidarity between different parts of the same struggle, sharing whenever possible—and when that’s not possible, permitting each other to continue on a more or less parallel path. In order that this solidarity can function, it is necessary to respect the immediate work some people focus on and at the same time not to denounce any group’s “radicalism” to the press or to the police.

It’s easy for someone who spends half of her earnings on rent to appreciate a law that caps rent; for someone who can’t afford private insurance to appreciate public health services; for someone who lives in a squatted apartment to appreciate a moratorium on evictions; for a migrant to appreciate legal protections against deportation. Those who don’t personally experience any of these situations should empathize with those who do before solidifying their political ideas.

At the same time, many of us who experience precariousness choose not to create an identity out of it. We have to get to the root of the problem. Public health and rent control are great, but legal reforms and “public” good are not under our control, they are under the control of the state, and they will do us no good when the state decides it’s inconvenient to maintain what they once gave us. Why has this pandemic resulted in such a grave crisis? Because the state has continually reduced the quality of public health services. Why has rent increased so much? Because the state passed the Urban Rental Law, stripping away protections won by previous generations.

Short-term measures are necessary, but we also need a revolutionary perspective, at least for whoever doesn’t want to spend their whole life fighting for crumbs, for mere survival.

Some Conclusions

Capitalism is global. States support one another at the global level. A revolution in one single place isn’t possible, at least not for the long term. An internationalist vision is essential in this time of pandemic, xenophobia, borders, and transnational corporations. In the Spanish state, internationalism has been pretty weak of late. In Latin America, there have been strikes and revolts for free public transportation, there have been right-wing coups, there have been months and months of struggle, and many deaths. Yet in the Spanish state, not a peep. In Hong Kong, there was almost an entire year of protests against new authoritarian measures. In the Spanish state, silence. For all of 2019, just on the other side of the Pyrenees, the yellow vests gave it their all fighting against austerity. How many rallies showing solidarity have there been in the Spanish state?

Movements for freedom and dignity and against exploitation must be global. Right now we’re suffering a global pandemic—and the strongest states, from the US to China, are responding with apathy and deadly incompetence or with a level of totalitarian surveillance (drones, real-time location surveillance of individuals, cameras in every public space that use facial recognition). In the Spanish state, we see a combination of incompetence and police authoritarianism.

The rent strike is already spreading through various neoliberal countries, where vast numbers of people are in danger of losing their homes. There is no doubt that this is also the situation here in the Spanish state. If we’re not capable of internationalizing our struggles now, will we ever be?

For solidarity and dignity, against precariousness. #RentStrikeNow

“It is necessary that nobody lives standing atop us

sucking our blood and denying us the right to live”-Virginia Bolten