To celebrate the birthday of Kenneth Rexroth, poet and anarchist, we have prepared this photoessay presenting his poem “Noretorp Noretsyh” painted across the walls and rooftops of three continents. We’ve added annotations illuminating Rexroth’s numerous historical references.

We don’t know anything about the painting, of course. We just found the photographs.

Rexroth is one of the unknown progenitors of contemporary anarchism. His work was formative for a generation of anti-authoritarians in the 20th century, but aside from a quotation1 in the book Desert, the average contemporary anarchist may not have heard of him at all.

After the Second World War, when radicalism had given way to authoritarianism worldwide, Rexroth was one of a small number of people who set the stage for the countercultural movements of the 1960s to emerge. One of the vehicles for this process of regeneration was a reading and discussion group called the Libertarian Circle, arguably a predecessor of the Berkeley Anarchist Study Group. In his autobiography, Rexroth recalls:

The place was always crowded, and when the topic of conversation for the evening was “Sex and Anarchy,” you couldn’t get in the doors. People were standing on one another’s shoulders, and we had to have two meetings, the overflow in the downstairs meeting hall.

There was no aspect of Anarchist history or theory that was not presented by a qualified person and then thrown out to discussion. Even in business or organizational meetings, we had no chairman or agenda, but things moved along in order and with dispatch. Our objective was to refound the radical movement after its destruction by the Bolsheviks, and to rethink all the ideologists from Marx to Malatesta… This also contributed to the foundation of the San Francisco Renaissance and to the specifically San Francisco intellectual climate.

Rexroth also maintained a program on the listener-supported Berkeley radio station KPFA, where the anarchist news project It’s Going Down offers a regular show today.

You can read Morgan Gibson’s biography Revolutionary Rexroth here. Ken Knabb, best known for translating the works of the Situationist International, has also written a biography, The Relevance of Rexroth, which is available online along with an archive of Rexroth’s work.

“Every revolution has been born in poetry, has first of all been made with the force of poetry… Real poetry […] brings back into play all the unsettled debts of history.”

Situationist International, “All the King’s Men”

Rexroth’s “Noretorp Noretsyh” uses the Hungarian uprising of 1956 as a point of departure to describe how history’s unsettled debts come back into play in every new upheaval. Omnia mutantur, nihil interit—everything changes, but nothing is lost.

Those who wish to read the poem in full first before taking in the art and annotations may jump to the appendix.

NORETORP-NORETSYH

The title spells out “hysteron proteron” backwards—the Greek rhetorical term for beginning with a later event and then referring to an earlier one in reverse chronological order. The first shall be last and the last shall be first, as it says in the Gospel of Matthew. Reversing the order of the letters, Rexroth further complicates the relationship between past and present. The poem that follows begins in the present and pans back to a past that continues to unfold, unconcluded.

A walking path, seen from above.

Rainy, smoky Fall

The poem is set during the Hungarian uprising that took place in fall 1956. Following Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, movements for political freedom and workers’ self-management gained ground in Hungary, peaking in late 1956—when the Soviet Union used tanks to reinstall a loyal puppet government in order to preserve Hungary’s status as a vassal state.

You can read a selection of anarchist and anti-state communist accounts of the uprising here. Though Stalinists have long sought to smear those who criticized the Russian invasion as advocates of capitalism or even fascism, principled Marxists also disapproved. In crushing the anti-capitalist opposition, the authorities in Moscow rendered it inevitable that when state socialism finally collapsed in the Eastern Bloc, it would be succeeded by capitalism and far-right nationalism.

The term “tankie” originated as a way to describe hardline party loyalists who supported the Russian invasion of Hungary.

The Pacific Northwest.

Clouds tower

In the brilliant Pacific sky.

The Midwestern United States.

In Golden Gate Park, the peacocks

Scream, wandering through falling leaves.

Peacocks inhabited San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park from the 19th century until at least the 1950s. A decade after the poem is set, the Diggers served free meals in the park at 4 pm, a precursor to Food Not Bombs; thirty years later, it was the site of the annual Bay Area Anarchist Book Fair. Today, there are no more peacocks in the park. Their screams, which represent immediate, present-day sensuous reality in the poem, reach us today as echoes alongside the other ghosts Rexroth summons.

Over a river that flows to the Atlantic Ocean.

In clotting nights in smoking dark,

The Kronstadt sailors are marching

Through the streets of Budapest.

In February 1921, after the conclusion of the Russian civil war, the crews of two Russian battleships stationed at the island naval fortress of Kronstadt held an emergency meeting in response to Communist Party crackdowns on labor organizing and peasants’ autonomy in the emerging Soviet Union. Many of these were the same sailors who had been on the front lines of the revolution that had toppled the Tsar in 1917. They agreed on fifteen demands, and rose in protest against the Soviet authorities.

The following month, on the 50-year anniversary of the Paris Commune, 60,000 Red Army troops under the command of Leon Trotsky carried out Lenin’s directive to crush the uprising at Kronstadt, killing and imprisoning thousands.

One of the best ways to learn about the goals and values of the Kronstadt uprising is to read the periodical that the provisional revolutionary committee published, which is available in English here in full. You can also read accounts from Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman.

Pacific Northwest.

The stones

Of the barricades rise up and shiver

Into form.

Two decades earlier, in 1936, Rexroth had treated the Kronstadt uprising in his poem “From the Paris Commune to the Kronstadt Rebellion”:

They go saying each: “I am one of many”;

Their hands empty save for history.

They die at bridges, bridge gates, and drawbridges.

Remember now there were others before;

The sepulchres are full at ford and bridgehead.

Richmond, Virginia.

They take the shapes

Of the peasant armies of Makhno.

Nestor Makhno was one of countless Ukrainian peasants who fought against a succession of occupying Tsarist, capitalist, and Communist Party troops in the course of the Russian Revolution of 1917-21.

“After seven years in the Tsar’s prisons, Makhno was released from prison by the upheavals of 1917. He eventually became a leader in the anarchist forces that fought in turn against Ukrainian Nationalists, German and Austro-German occupiers, the reactionary Russian White Army, the Soviet Red Army, and various Ukrainian warlords in order to open a space in which anarchist collective experiments could take place. Makhno and his comrades repeatedly bore the brunt of the White Army attacks, while Trotsky alternated between attacking them with the Red Army and signing treaties with them when the Soviets needed them to keep the reactionary White Army at bay. On November 26, 1920, a few days after Makhno had helped to definitively defeat the White Army, the Red Army summoned him and his comrades to a conference. Makhno did not go; the Bolsheviks summarily murdered all of his comrades who went.”

Makhno and the other surviving rebels continued fighting—but as the Red Army was now able to concentrate all its forces on them, they were forced to flee into exile in August 1921. Makhno died of tuberculosis in Paris in 1934. The best introduction to Makhno’s story remains Alexandre Skirda’s biography.

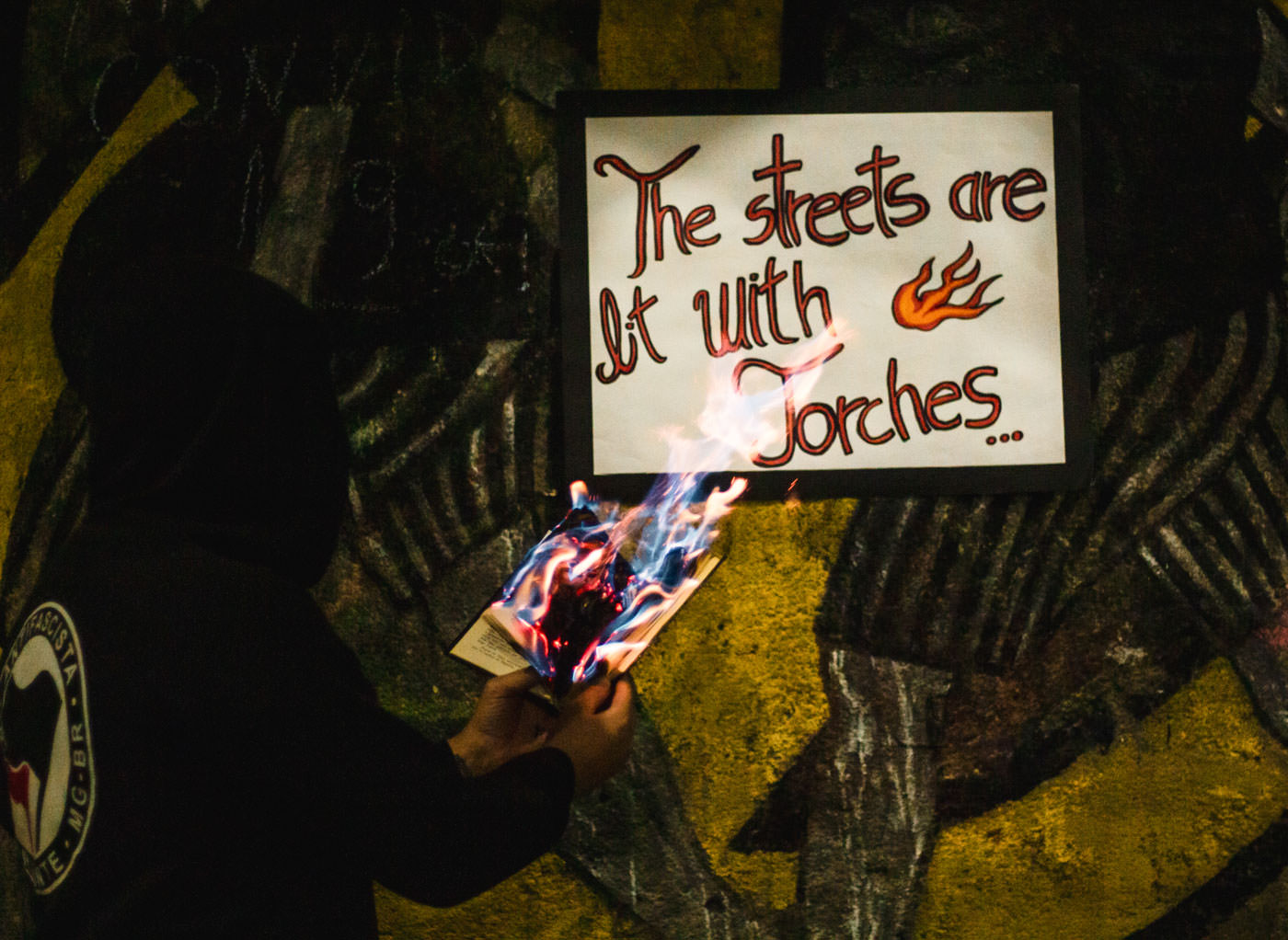

Brazil.

The streets are lit with torches.

The American South.

The gasoline drenched bodies

Of the Solovetsky anarchists

Burn at every street corner.

After the Communist Party defeated the opposition in the Russian civil war of 1918-1921, they exiled anarchist and communist dissidents to the Solovetsky Islands, creating one of the first prisons of the Gulag system (G(lavnoe) u(pravlenie ispravitelʹno-trudovykh) lag(ereĭ), “Chief Administration for Corrective Labor Camps”).

The ancient monasteries in the town of Suzdal and on the Solovetskii Islands in the White Sea were converted into prisons for hundreds of political offenders, who staged demonstrations and hunger strikes to protest their confinement. A few desperate souls resorted to self-immolation, following the example of the Old Believers who, 250 years before, had made human torches of themselves while barricaded in the Solovetskii Monastery. During the mid-1920s, the anarchists were removed from Solovetskii and dispersed among the Cheka prisons in the Ural Mountains or banished to penal colonies in Siberia.

-Paul Avrich, The Russian Anarchists

Rust Belt, USA.

Kropotkin’s starved corpse is borne

In state past the offices

Of the cowering bureaucrats.

The widely known anarchist author and scientist Peter Kropotkin returned to Russia in 1917 after four decades of exile. Desiring to legitimize Bolshevik authority with the reputation of a universally respected anarchist, Vladimir Lenin maintained cordial relations with him, without taking his concerns seriously.

In March 1920, Kropotkin wrote to Lenin to report the desperate hunger of the postal-telegraph department employees in his town. He argued that because the peasants and workers had not established any local self-managed structures, but rather had been put at the mercy of a vastly inefficient bureaucratic system, they were unable to meet their basic needs, while the relief provisions promised by the government were two months late:

I consider it a duty to testify that the situation of these employees is truly desperate. The majority are literally starving. This is obvious from their faces. Many are preparing to leave home without knowing where to go. And in the meantime, I will say openly that they carry out their work conscientiously… to lose such workers would not be in the interests of local life in any way.

On October 15, 1920, the following news item appeared in the New York Times from a correspondent in Berlin:

KROPOTKIN IS STARVING.

Prince Kropotkin is dying of hunger. One of the German trade unions has received information that the veteran political fighter is suffering so much from want of food and clothing that his death is practically certain during the coming Winter.

Kropotkin is now 78 years of age. His whole wealth always has been devoted to the cause of democracy and the report referred to, which there is no reason to doubt, paints a sad picture of the misery of the grand old man and his daughter Sascha.

An appeal is being made by Socialists of all sections here to send help to the Prince and his daughter, and it is hoped this will reach them through the Red Cross Society. It is also hoped that the Russian Government will be persuaded to grant Kropotkin and his daughter a pass to Italy or Switzerland, which hitherto has been refused. There they would be looked after by friends.

Peter Kropotkin passed away a few months later, on February 8, 1921.

Kropotkin’s funeral on February 13 was arguably the last anarchist demonstration permitted in Russia until the fall of the Soviet Union. Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman and many other prominent anarchists participated. They managed to exert enough pressure on the Bolshevik authorities to compel them to release seven anarchist prisoners for the day; the Bolsheviks claimed that they would have released more, but the others supposedly refused to leave prison. Victor Serge recounts how Aaron Baron, one of the anarchists who was temporarily released, addressed the mourners from Kropotkin’s graveside before vanishing into the jaws of the Soviet carceral system.

You can see footage of Kropotkin’s funeral here.

Rexroth had referenced Kropotkin starving to death in an earlier poem, “August 22, 1939,” named for the date of the executions of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in the United States:

Kropotkin dying of hunger,

Berkman by his own hand,

Fanny Baron biting her executioners,

Makhno in the odor of calumny,

Trotsky, too, I suppose, passionately, after his fashion.

Do you remember?

What is it all for, this poetry,

This bundle of accomplishment

Put together with so much pain?

–“August 22, 1939,”

The Fanny Baron he references here is Fanya Baron, Aaron Baron’s spouse, who was shot without trial by the Russian authorities in September 1921. Trotsky excused the execution on the grounds that she and the other twelve anarchists detained with her were not “real anarchists, but criminals and bandits who cover themselves by claiming to be anarchists.”

Northern Germany.

In all the Politisolators

Of Siberia the partisan dead are enlisting.

The “Politisolators” (Political Isolation Camp) were institutions within the Gulag system in which anarchists, communists who had fallen out of favor with the Party, and others were entombed—much as anarchists and other political prisoners in the United States have recently been buried in Communications Management Units (CMUs).

Arizona.

Berneri, Andreas Nin,

Are coming from Spain with a legion.

Luigi Camillo Berneri was a well-known Italian anarchist organizer who traveled to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War. He was offered a position in the Council of the Economy, but refused to participate in the government.

When clashes between anarchists and the Stalin-controlled Communist Party broke out in Republican Spain, the house Berneri shared with several other anarchists was attacked. He and his comrades were labeled “counter-revolutionaries,” disarmed, deprived of their papers, and forbidden to go out into the street. On May 5, 1937, Stalinists murdered Berneri along with another Italian anarchist, Francisco Barbieri.

Andrés Nin was involved in the leadership of the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) in Spain until 1937. The month after Berneri was murdered—at the height of the civil war against Franco—the Spanish Communist Party pressured the Spanish Republican government into declaring the POUM illegal and arresting much of the leadership, including Nin. He was tortured and murdered under the supervision of Russian agents.

Austria.

Carlo Tresca is crossing

The Atlantic with the Berkman Brigade.

Carlo Tresca was an Italian-American newspaper editor and labor organizer involved with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). A friend of Julia Poyntz, he spoke out when she was apparently disappeared by the Russian secret police. Tresca was murdered in 1943, likely by organized crime. Nunzio Pernicone’s biography is an excellent source on Tresca’s life.

The Berkman Brigade is likely a fanciful reference to the Lincoln Battalion, a international group of communist volunteers who fought in the Spanish Civil War. Longtime anarchist author and organizer Alexander Berkman passed away in June 1936. Had international anarchist volunteers converged in Hungary in 1956 to fight against the occupying Russian forces—a flight of fancy, to say the least, as most anarchists had been imprisoned or killed by then—they might well have organized under such a banner.

East Coast of the United States.

Bukharin has joined the Emergency

Economic Council.

Starting out as a left communist, Nikolai Bukharin swung to what was described as the right wing of the Bolshevik party. He rose to the upper ranks of the Communist Party, ultimately working with Stalin to expel Trotsky and their other colleagues from power. Promoting economic liberalization, he clashed with Stalin over collectivization, and was executed March 15, 1938.

“I feel helpless before a hellish machine,” Bukharin allegedly confessed to his wife shortly before his execution, exhorting her to memorize his last testament: “Know, comrades, that on that banner, which you will be carrying in the victorious march to communism, is also a drop of my blood.”

It is interesting that Rexroth chose to include Bukharin, whose politics hardly resonated with him. Arguably, in Rexroth’s poetic resurrection of the dead, each figure gets the opportunity to redeem his or her own errors as well as avenging defeats.

Next to an occupied community garden.

Twenty million

Dead Ukrainian peasants are sending wheat.

The reference is to the series of famines that struck Ukraine during the upheavals of the early 20th century, including the Holodomor famine of 1932-33 in which millions of Ukrainians died of starvation. Most historians number the dead significantly lower than Rexroth’s estimate, with the low estimates beginning at 3 million—still a lot of deaths by any measure. Some charge that Stalin deliberately sought to kill off an unruly part of the population by intentional mismanagement.

The issue has been confused by right-wing reactionaries who have sought to utilize the story of the Holodomor to justify their own authoritarian projects. Yet capitalism, too, has produced countless famines and needless deaths—as has fascism. Returning to Kropotkin’s letter to Lenin, the question is how to organize the distribution of resources and power in such a way that no one is able to deny anyone else access to what they need to survive.

A hospital during the COVID-19 crisis.

Julia Poyntz is organizing American nurses.

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, a hereditary member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and, later, a class president and valedictorian, Julia Poyntz described herself in 1912 as “a woman’s suffragist or worse still a feminist and also a socialist (also of the worst brand).” Joining the Communist Party in hopes of advancing the cause of the working class, she became involved with the Russian secret police, then distanced herself from the Party in 1936, disillusioned with its methods. She disappeared without a trace in early June 1937, the same month that Andrés Nin was murdered. It is widely believed that she was kidnapped and executed by the Russian secret police.

Midwestern United States.

Gorky has written a manifesto

“To the Intellectuals of the World!”

Maxim Gorky grew up in Tsarist Russia in extreme poverty. He came to be a successful writer, a voice of the Russian underclass. Gorky participated in the socialist movement alongside the Bolsheviks, though there was often friction between him and members of the intelligentsia like Lenin and Trotsky. Disappointed with Communist Party repression of socialists in Russia, he lived outside of Russia from 1921 on. In the end, he made peace with the Stalinist authorities and returned to his homeland, where he died of pneumonia under house arrest in June 1936.

The Bay Area where Kenneth Rexroth lived.

Mayakofsky and Essenin

Have collaborated on an ode,

“Let THEM Commit Suicide.”

Sergei Yesenin (Essenin) and Vladimir Mayakovsky were among the most successful poets of the early Soviet Union. Invigorated by the struggles of the Russian Revolution but stifled by the atmosphere that emerged afterwards, both of them committed suicide—Yesenin in 1925, Mayakovsky in 1930.

The concluding lines of Yesenin’s final poem read:

Don’t stir up the old expectations;

Don’t wake up all that didn’t come true—

I’ve endured loss and much exhaustion,

Yes, and endured them quite early, too.

Determined to keep his head in the fight, Mayakovsky responded to the dead Yesenin’s poem with a living poem of his own:

Isn’t it truly absurd,

allowing cheeks to flush with deathly hue?

You who could do such amazing things with words

that no one else on earth could do?…Forward march! Let time burst behind us like rockets in the air.

Let the wind blowing back to the old days carry

Nothing but clumps of our hair.

Our planet is poorly equipped for delight.

We have to snatch our joy from the days to come.

In this life

it’s not difficult to die.

To make life

is more difficult by far.

But Mayakovsky, too, was ultimately crushed. In his last published poem, “At the Top of My Voice,” he cries out to us across a century of totalitarianism and tragedy, investing every phrase with double meanings in order to speak to us, today, across the heads of the officials who made him a public icon while policing his work:

Agitprop sticks in my teeth too,

and I’d rather compose romances for you—

more profit in it

and more charm.But I subdued myself,

setting my heel on the throat of my own song.Listen, comrades of posterity,

to the agitator, the rabble-rouser.Stifling the torrents of poetry,

I’ll skip the volumes of lyrics;

as one alive,

I’ll address the living.

I’ll join you

in the far communist future,

I who am

no Yesenin super-hero.My verse will reach you

across the peaks of ages,

over the heads

of governments and poets. […]When I appear before the Party’s Central Control Commission of the coming

bright years,

by way of my Bolshevik party card, I’ll raise

above the heads

of a gang of self-seeking

poets and rogues,

all the hundred volumes

of my

communist-committed books.

Here is Mayakovsky’s own suicide note, written in April 1930 in the comparative liberty of one who has chosen death over keeping up appearances:

It’s after one. You’ve likely gone to sleep.

The Milky Way streams silver, a river through the night.

I don’t hurry, I don’t need to wake you

Or bother you with lightning telegrams.

Like they say, the incident is closed.

Love’s little boat has crashed against the daily grind.

We’re even, you and I. No need to tally up

Mutual sorrows, mutual pains, and wrongs.

Look: How quiet the world is.

Night cloaks the sky with the tribute of the stars.

At times like these, you can rise, stand, and speak

To history, eternity, and all creation.

Paris, France.

In the Hungarian night

All the dead are speaking with one voice,

Over the Mississippi River.

As we bicycle through the green

And sunspotted California

November.

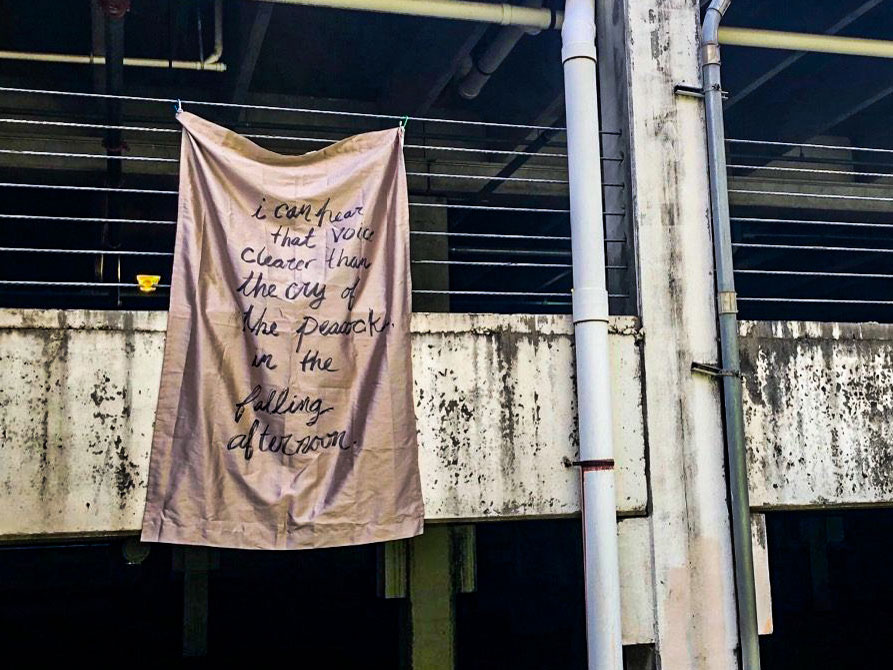

A parking deck in the Southern United States

I can hear that voice

Clearer than the cry of the peacocks,

In the falling afternoon.

New York City.

Like painted wings, the color

Of all the leaves of Autumn,

Detroit.

The circular tie-dyed skirt

I made for you flares out in the wind,

Over your incomparable thighs.

Near the end of the poem, we encounter a historical enigma. It was written in 1956-57, intended for an issue of the Evergreen Review. Yet it is widely believed that the expression “tie-dye” did not appear until a decade later, when the practice was popularized in the Bay Area—some, indeed, attribute it to the aforementioned Diggers. Did Rexroth invent tie-dyeing a decade before its acknowledged origins?

“Indubitably: things do not begin; or they don’t begin when they are created. Or the world was created old,” as Macedonio Fernandez put it in his novel, The Museum of Eterna’s Novel. Fernandez, another little-remembered yet influential anarchist author, was Jorge Borges’s quasi-fictitious mentor.

Southern California.

Oh splendid butterfly of my imagination,

Flying into reality more real

Than all imagination,

In an expression of despair, Rexroth attributes more reality to the realpolitik of the Soviet Union and its toadies than all the desperate bids for freedom born in the imaginations of the oppressed.

At an abandoned recreation center somewhere in the United States, during the COVID-19 lockdown.

the evil

Of the world covets your living flesh.

Though Rexroth ends on this grim note, we must not read him as a mere pessimist. Earlier in his aforementioned poem “August 22, 1939,” Rexroth holds out an ambiguous hope that the struggle against authoritarianism might be nearing its conclusion, even as he reckons its scale on the level of millennia, as Fredy Perlman did:

These are the last terrible years of authority.

The disease has reached its crisis,

Ten thousand years of power,

The struggle of two laws,

The rule of iron and spilled blood,

The abiding solidarity of living blood and brain.

Detroit.

Appendix

“NORETORP-NORETSYH”

Rainy, smoky Fall, clouds tower

In the brilliant Pacific sky.

In Golden Gate Park, the peacocks

Scream, wandering through falling leaves.

In clotting nights in smoking dark,

The Kronstadt sailors are marching

Through the streets of Budapest.

The stones

Of the barricades rise up and shiver

Into form.

They take the shapes

Of the peasant armies of Makhno.

The streets are lit with torches.

The gasoline drenched bodies

Of the Solovetsky anarchists

Burn at every street corner.

Kropotkin’s starved corpse is borne

In state past the offices

Of the cowering bureaucrats.

In all the Politisolators

Of Siberia the partisan dead are enlisting.

Berneri, Andreas Nin,

Are coming from Spain with a legion.

Carlo Tresca is crossing

The Atlantic with the Berkman Brigade.

Bukharin has joined the Emergency

Economic Council.

Twenty million

Dead Ukrainian peasants are sending wheat.

Julia Poyntz is organizing American nurses.

Gorky has written a manifesto

“To the Intellectuals of the World!”

Mayakofsky and Essenin

Have collaborated on an ode,

“Let THEM Commit Suicide.”

In the Hungarian night

All the dead are speaking with one voice,

As we bicycle through the green

And sunspotted California

November.

I can hear that voice

Clearer than the cry of the peacocks,

In the falling afternoon.

Like painted wings, the color

Of all the leaves of Autumn,

The circular tie-dyed skirt

I made for you flares out in the wind,

Over your incomparable thighs.

Oh splendid butterfly of my imagination,

Flying into reality more real

Than all imagination,

the evil

Of the world covets your living flesh.

-

“It is my opinion that the situation is hopeless, that the human race has produced an ecological tip over point… but assuming there is a possibility of changing the society’s “course in the darkness deathward set,” it can only be done by infection, infiltration, diffusion and imperceptibility, microscopically throughout the social organism, like the invisible pellets of a disease called Health.” -Kenneth Rexroth, “Radical Movements on the Defensive,” San Francisco Magazine, July 1969. ↩