On the occasion of the birthday of Yugoslavian director Dušan Makavejev, who passed away last year, we explore what his classic 1971 film WR: Mysteries of the Organism has to offer today’s struggles against nationalism, fascism, and dogmatism.

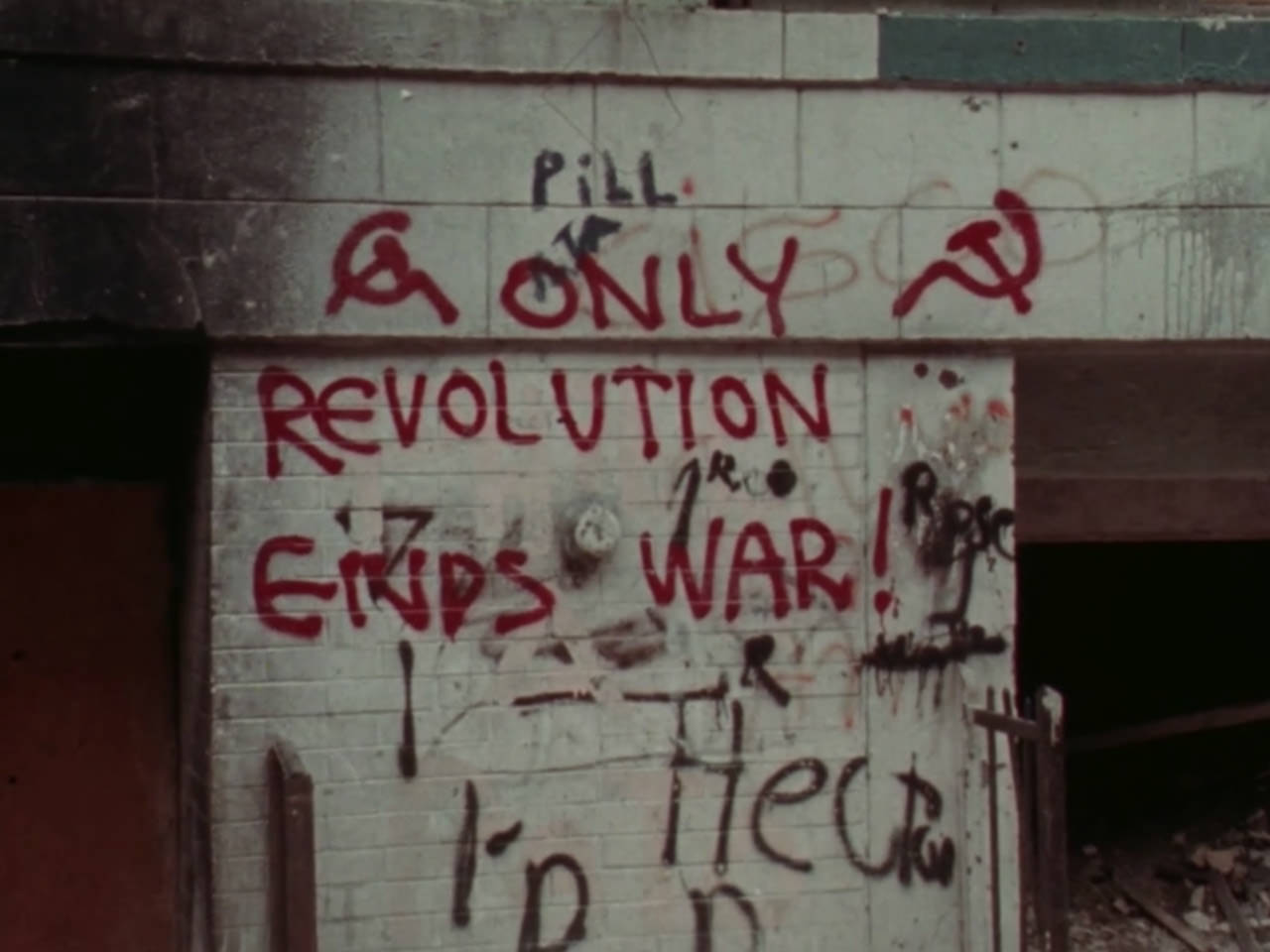

Nowadays, when we think of resisting fascism, we think of collecting intelligence on avowed fascists, doxxing them, deplatforming them, physically confronting them and the police who defend them—in short, we think of a very narrow range of activities, strategies, and desires. Yet in the mid-20th century, anti-fascism was a much broader philosophical, scientific, and aesthetic current extending from the Surrealists to the Existentialists, from Wilhelm Reich and Theodore Adorno to Suzanne and Aimé Césaire, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guatarri, and Dušan Makavejev.

Today, in the Trump era, as in the mid-20th century, authoritarianism is not an aberration, but a norm grounded in a deeply repressive and hierarchical society. Like our predecessors, we have to combat it on every level, using a wide range of strategies and tools—from street tactics to pedagogy, philosophy, and cinema. This is the spirit in which we turn our thoughts to Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism.

The following essay was solicited for and published in the second issue of Antipolitika, the premier Balkan anarchist journal, in a theme issue engaging with the legacy of Yugoslavia. All texts from both issues of Antipolitika—issue 1 on militarism and issue 2 on Yugoslavia—are available in English here. Antipolitika is also printed in Serbo-Croatian and Greek. A third issue on the topic of nationalism is currently in preparation.

You can order print copies of Antipolitika here. You can also download this text as a zine to print and distribute.

WR: Mysteries of the Organism—Beyond the Liberation of Desire

Anarchism, crushed throughout most of the world by the middle of the 20th century, sprang back to life in a variety of different settings. In the US, it reappeared among activists like the Yippies; in Britain, it reemerged in the punk counterculture; in Yugoslavia, where an ersatz form of “self-management” in the workplace was the official program of the communist party, it appeared in a rebel filmmaking movement, the Black Wave. As historians of anarchism, we concern ourselves not only with conferences and riots but also with cinema.

Of all the works of the Black Wave, Dušan Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism stands out as an exemplary anarchist film. Rather than advertising anarchism as one more product in the supermarket of ideology, it demonstrates a method that undermines all ideologies, all received wisdom. It still challenges us today.

The struggle of communist partisans against the Nazi occupation provided the foundational mythos for 20th-century Yugoslavian national identity. After the Second World War, the Yugoslavian state poured millions into partisan blockbusters like Battle of Neretva and other sexless paeans to patriotic self-sacrifice. These films depicted a world of moral binaries: heroism versus cowardice, austerity versus indulgence, communism versus fascism.

A poster for Battle of Neretva, a classic of overt militarism and repressed sexuality. Compare this with the closing scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s North By Northwest.

At the same time, Tito’s break with Stalin in 1948 set the stage for the Yugoslavian experiment with socialism to take its own road. Geopolitically, Yugoslavia represented a third power alongside the Eastern and Western Blocs; economically, “self-management” was official government policy; socially, Yugoslavia supposedly offered a more tolerant and egalitarian alternative to US capitalism and Soviet totalitarianism.

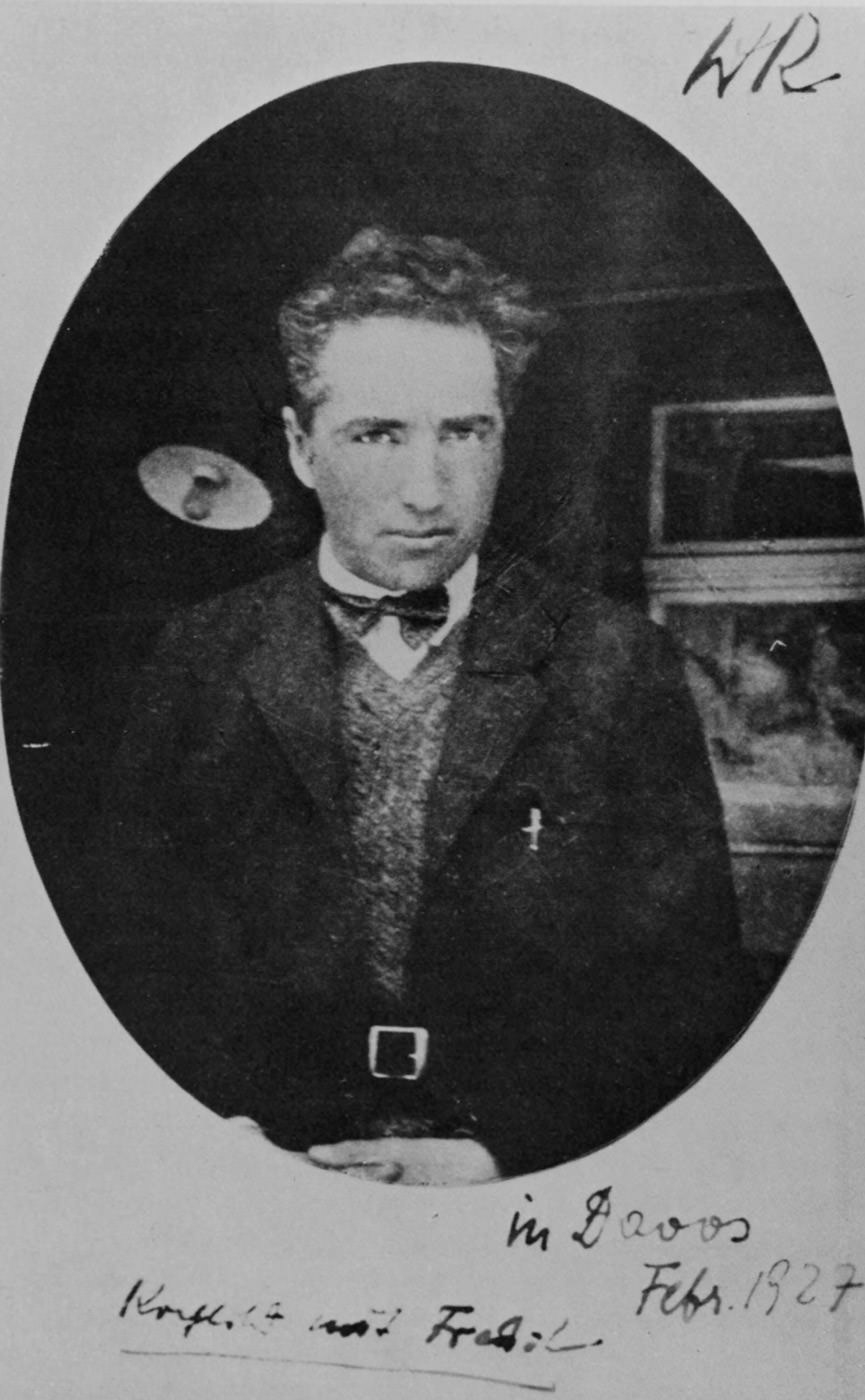

Makavejev set out to test the limits of Yugoslavian permissiveness. Exploring the variants of Marxism, he found a road not taken in the works of the Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. A protégé of Sigmund Freud, Reich had founded the German Association for Proletarian Sexual Politics (Sex-Pol) to promote sexual liberation; in books like The Mass Psychology of Fascism, he sought to identify the role of psychological factors in the rise of authoritarianism. Hounded out of the Communist Party by pro-Soviet puritans and driven from Europe by the Nazi seizure of power, Reich fled to the United States. He died in prison, having spent the final years of his life as a crank promoting orgone accumulators, cloudbusters, and other pseudoscientific inventions, convinced he was still the target of “red fascist” persecution as the Food and Drug Administration burned his books.

Wilhelm Reich in 1927.

Traveling to the United States in Reich’s footsteps, Makavejev interviewed Reich’s remaining disciples and recorded footage of therapists, artists, and entrepreneurs associated with what Reich had dubbed the sexual revolution. Returning home, he filled out the material with clips from Soviet propaganda films like The Vow and shot a fictional sequence of his own.

The fictional sequence forms the backbone of WR’s unconventional plot, dividing the film into two “Sex-Pol” shorts. The first 25 minutes is ostensibly a documentary about Wilhelm Reich and his legacy in the US, captioned “May 1, 1931, Berlin”—when Reich’s original Sex-Pol might have made this film, in the alternate universe Makavejev concocts. The remainder of the film, captioned “May 1, 1971 Belgrade,” is set in an imagined Yugoslavia, in which the protagonist, Milena,1 attempts to implement Reich’s philosophy as a form of orthodox party communism.

WR: Mysteries of the Organism earned cult status when it was first screened in 1971, but the socialist authorities set out to suppress it almost immediately. The film was banned in Yugoslavia for a decade and a half.2 Makavejev himself was driven into exile in the West following a complaint brought against him by veteran partisans.

Speaking to an interviewer in 1995, Makavejev attributed the banning of WR to the continuing influence of the Soviet Union in Yugoslavia. Yet the capitalist West was ultimately no more supportive of his iconoclastic filmmaking. In view of his tribulations on both sides of the divide, we can see that the repression Makavejev exposed and experienced was not confined to a single national context, but characterizes every nation under capitalism and communism alike.

Wilhelm Reich and his family in exile in Maine.

“There is nothing in this human world of ours that is not in some way right, however distorted it may be.”

This quotation, which Makavejev attributes to Wilhelm Reich, is the key to understanding the whole film. Setting out to expose the distortions that repression has inflicted on humanity, Makavejev presents one of the 20th century’s fiercest denunciations of authoritarianism. Yet his ultimate motives are compassionate and affirmative. He is like a physician trying to diagnose the ailments afflicting the patient and the medical profession at once; this is why the film can appear so self-contradictory.

Given two ostensibly opposing positions, Makavejev always refuses to take sides, instead revealing the common threads that connect them. Then he introduces a third possibility as a counterpoint to the first two, and this serves as a point of departure for a new opposition to be transcended via the same method. In this way, he undermines and transforms the binaries that were essential to both Yugoslavian cinema and Cold War politics.

Beginning with Marxism and the (puritanical, repressive) Soviet Union on one side and capitalism and Western (commodified, exploitative) sexual liberation on the other, Makavejev takes the teachings of Wilhelm Reich as the basis for an imagined Yugoslavia representing a communist model for sexual liberation.3 Then he mounts a critique of sexual liberation as ideology, portraying an alternative communism in which sexual liberation could be as repressively realized as workers’ liberation was under Tito.

Like the Dadaists before him, Makavejev presents his critique via collage: montage is his answer to dialectics. He juxtaposes his documentary footage from the US with propaganda films from the Soviet Union, communist China, and Nazi Germany, along with his own fanciful Yugoslavian propaganda film. It is as if the viewer is switching between several different channels with both the soundtracks and the themes bleeding over from one to the next; each transition complicates and intensifies the web of associations.

For example, following a portrait of the conservative townspeople in the part of Maine where Reich settled, Makavejev cuts back to the streets of New York City, presenting Andy Warhol starlet Jackie Curtis promenading through the bright lights of the business district with her boyfriend. Over this scene, Makavejev dubs a radio commercial: “You own the sun with Coppertone.” The US is at once a bastion of small-town conservatism and a land of freedom in which sexual difference manifests as the commodification of the self on the market of identity. Provincial intolerance alongside the repressive tolerance of the metropolis—what Herbert Marcuse called “repressive desublimation.”

In the opening scene of WR: Mysteries of the Organism, Makavejev decodes the undertones of the famous Mao Tse-tung quotation, “If you want to make an omelette, you’ve got to break a few eggs,” regarding sex, reproduction, and destruction.

The protagonist of the sequences set in Yugoslavia is Milena, an apostle of Wilhelm Reich’s prescriptions for sexual liberation. Milena is the ideologue incarnate: passionate and doctrinaire, she has substituted advancing the party line for the actual fulfillment of her program. We see her reading Reichian propaganda, smoking a cigar à la Sigmund Freud, and sitting in her orgone accumulator while her housemate, Jagoda, makes love.

Milena’s voice in the film is also Reich’s voice, but behind that, it is Makavejev’s voice—the voice of a Yugoslavian making a documentary about Reich. Milena is Makavejev’s double, a dogmatic sendup of his own interest in Reich’s ideas as an emancipatory program—and of Yugoslavia’s dalliance with Marxism. Milena’s martyrdom is an allegory of Reich’s persecution and exile, foreshadowing Makavejev’s own misfortunes in his homeland and then in the West.

In the most famous scene of WR, Milena steps out onto the balcony of her apartment to harangue her neighbors in a sequence that channels the greatest Soviet propaganda films. “Socialism must not exclude human pleasure from its program!” she declaims to proletarian applause, a demagogue of sexual freedom. “The October Revolution was ruined when it rejected free love!” (The camera cuts to her housemate Jagoda, who gasps “War of liberation!” as she tries—playfully?—to escape her male lover.) “Frustrate the young sexually and they’ll recklessly take to other illicit thrills… political rallies with flags flying, battling the police like pre-war Communists! What we need is a free youth in a crime-free world!”

Clad in a mini-dress and an army jacket, Milena builds to her climax. “Sweet oblivion is the masses’ demand! Deprive them of free love and they’ll seize everything else! That led to revolution. It led to Fascism and Doomsday!” At first viewing, it could appear that Milena is championing sexual liberation. In fact, she is laying out a prescription for repressive desublimation as a vaccine against revolution.

The scene ends like a classic partisan film, with everyone singing a Yugoslavian folk song together—and suddenly, the film cuts to a rally in Beijing at which tens of thousands of people are raising Mao’s little red book in the air in unison. Stalin, glamorized in a Soviet propaganda film, strides out to the tune of a zither: “We have demonstrated our ability not only to destroy the old order, but to build in its place a new socialist order.”

This is the problem—how order succeeds order, the dictator replacing the Tsar just as Oedipus replaced his father. The film cuts to a scene in which an inmate in a mental hospital is undergoing electric shock therapy, and the zither resumes, driving home the association between patriarchal leadership, state power, and the institutional enforcement of mental health. The norms of sexual liberation are no more liberating than the norms of Marxism, which are no more liberating than the norms of capitalism.

Milena smoking a cigar like Sigmund Freud or Che Guevara.

As the movie shifts into high gear, Milena goes to see a Russian figure skating troupe perform. She and her housemate are in the company of two young soldiers: “Consider yourself protected by the Yugoslav People’s Army,” one says flirtatiously.

“But who will protect me from you?” Milena’s housemate responds.

Milena is not impressed by low-ranking Yugoslavian soldiers. She sets her sights on the star Russian figure skater. He is nationalistic manhood personified; the stage makeup of his profession only accentuates his icy masculinity. When she approaches him backstage for an autograph, he recites his answers directly out of a Communist Party phrasebook. His name is Vladimir Ilich—an overt reference to Lenin.

Milena’s attraction to Vladimir Ilich underscores the point that our current desires will not necessarily lead us out of the order that produces them. (“You are locked into your suffering,” sings Leonard Cohen, “and your pleasures are the seal.”) Earlier in the film, we hear Jackie Curtis describe her lover Eric as “an American hero” while Tuli Kupferberg prowls Manhattan with a toy machine gun, aping a US soldier. At the opening of the movie, Kupferberg4 intones, “He who chooses slavery—is he a slave still?”

Milena takes Vladimir Ilich back to her apartment to introduce the haughty Russian to the ideas of her mentor, Wilhelm Reich. “His name is World Revolution,” she explains, giving us another way to decode the title of the film. “He teaches that every nice person like you and me hides behind his façade a great explosive charge… A great reservoir of energy that can be released only by war or revolution.”

“In me? Me too?” interrupts Milena’s housemate, having stripped naked. “Love and crime. Give me some.“

At this moment, to the sound of a madcap Balkan horn line, Milena’s ex-lover, the lumpen-proletarian Radmilović, comes smashing through the wall like a cartoon superhero out of Deleuze and Guattari.5 Radmilović functions as a sort of Shakespearean fool: because he is a sexist, drunken lout, he can say and do things that would otherwise be inadmissible in Yugoslavian film. When we first encounter him, he is barricading a road; he accuses a BMW driver of being a member of the red bourgeoisie. Makavejev puts his own anarchistic ideas in the mouth of a communist caricature of an anarchist in order to save the authorities the trouble of having to caricature him themselves—a comic lampoon of a timeless socialist tactic.

Interrupting the conversation about Reich, Radmilović cheerfully hustles Vladimir Ilich into a wardrobe and commences nailing it shut. Milena is mortified: “Free the People’s Artist!”

The Id traps the Superego in the closet: turnabout is fair play!

Milena attempting to explain to Vladimir Ilich how patriarchal power and personality structure figure in the emergence of fascism. “Speaking truth to power” is a time-honored liberal strategy—and if it generally fails, it is not only because power is unimpressed by truth, but also because the speaker is usually not aware of the footholds the attraction to power has already established within her.

The scene returns to New York, where Nancy Godfrey is preparing to make a plaster cast of New York entrepreneur Jim Buckley’s phallus. While Godrey massages Buckley to erection, we see Milena reading aloud from Lenin’s The State and Revolution, in which Lenin quotes Engels:

“The proletariat needs the state, not in the interests of freedom, but in order to subdue its enemies, and as soon as it becomes possible to speak of freedom, the state as such ceases to exist.”

In other words, the state (the concentration of power and authority in the hands of a few) is to create the conditions for freedom (the distribution of power and agency to all on a horizontal basis). “Kill for Peace” by The Fugs kicks in on the soundtrack, a comparably oxymoronic program.

As Godfrey packs plaster around Buckley’s erection, the soundtrack shifts to Czech classical composer Bedřich Smetana’s patriotic theme, “The Moldau.” Smetana’s composition connects naturalism and nationalism, evoking the reverence with which male sexual potency is venerated in patriarchal society. The camera cuts briefly to Jackie Curtis paying obeisance at a Catholic shrine; the virginal saint above her is holding a skull. Briefly, we glimpse Milena releasing Vladimir Ilich from the wardrobe.

In the plaster casting scene, Makavejev is depicting the reduction of living sexuality to a commodity, an inert representation. What seems like a celebration of manhood and male power is actually a substitution tantamount to castration: the inorganic for the organic, the artificial for the real, the rigid for the flexible, the statue of the hero for the flesh of the human being. Those who seek patriarchal status and political power willingly make this exchange, not understanding that these supplant rather than supplement their personhood.

The classic example of this is Lenin’s corpse, preserved in Red Square for workers to file dutifully past. Posters around the USSR blazoned Vladimir Mayakovsky’s words: “Even now, Lenin is more alive than the living.” Raised to superhuman status as an icon, Lenin not only ceased to be a living, breathing human being—he also drained others of life and freedom.6

When the duplication of Buckley’s organ is complete, WR jumps back to the Soviet propaganda reel, equating Stalin with the ersatz phallus. “Comrades, we have successfully completed the first stage of communism!” Stalin proclaims, joining everyone in applauding his own declaration.

This is Makavejev at his bitterest. Stalin’s “first stage of communism” is the reduction of life to inorganic matter—the substitution of duplicate for original, of ideology for experience, of program for desire, of permanence for presence, of power for pleasure, of nation for people. The film cuts to a man in a straitjacket slamming his head against a wall over and over to the sound of another communist hymn: “We thank the Party—our glorious Party—for bringing happiness to every home.”

At a time when the Yugoslavian government relied on filmmaking as one of the chief means of promoting patriotism and obedience, Makavejev was a mutineer turning his weapon against his superiors. Today, when access to the means of media production has become so widespread, it’s difficult to grasp how forcefully subversive this was in 1971.

The balcony scene—arguably, one of the high points of world cinema.

The argument thus formulated, WR speeds towards its catastrophic conclusion. Milena and Vladimir Ilich are walking through a snowy park together. Finally, they kiss, and, as the soundtrack swells with plaintive violins, Vladimir Ilich soliloquizes about Beethoven:

Nothing is lovelier than the Appassionata. I could listen to it all day! Marvelous, superhuman music! With perhaps naïve pride, I think, “What wonders men can create!” But I can’t listen to music. It gets on my nerves!

It arouses a yearning in me to babble sweet nothings, to caress people living in this hell who can still create such beauty. But nowadays, if you stroke anybody’s head, he’ll bite your hand off! Now you have to hit them on the head. Hit them on the head mercilessly, though in principle we oppose all violence!

At the culmination of this speech, he strikes Milena for attempting to touch him.

These words, of course, are straight from Lenin’s mouth, via Gorky’s memoirs of the Great Leader. As the ultimate homo politicus, Lenin feared eruptions of strong feeling. From the perspective of the tactician, all sentiment should be strategic, all raw energy should be channeled into rationalized systems. In place of spontaneous expressions of love for humanity, merciless violence.

Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary anarchist, is also remembered for his love of Beethoven’s music. Yet he never fled from his passions. In Paris, he lived with a pianist so as to hear Beethoven every day. Shortly before the final uprising of the revolutions of 1848-49, Bakunin went to hear his favorite composition, the 9th Symphony, performed in Dresden; afterwards, he was accused of burning down the opera house in which it had been performed. In 1876, in the final weeks of his life, he set out on one last journey to visit the pianist one more time: “All this will pass away,” Bakunin confided to him, “but the Ninth Symphony will remain.”7

In the contrast between these two Russian revolutionaries, we see two fundamentally different ways of relating to the tides of emotion that surge through us. On Lenin’s side, we see control, austerity, order, violence. On Bakunin’s side, freedom, indulgence, excess, passionate love, the river bursting its banks.

Shocked at his own aggression, Vladimir Ilich entreats Milena to forgive him. Furious, she responds:

You love all mankind, yet you’re incapable of loving one individual, one single living creature! What is this love that makes you nearly knock my head off? You said I was as lovely as the revolution. But you couldn’t bear the “Revolution” touching you!

Milena’s indictment of Vladimir Ilich is Reich’s indictment of Lenin and Hitler and Stalin; it is Makavejev’s indictment of Tito and of all patriarchal power and personality structure. It’s also one of the fiercest expressions of disillusionment with state socialism to reach us from the 20th century.

As Milena concludes her speech, Vladimir Ilich embraces her, remorseful and abashed. They make love.

Then, unhinged by postcoital shame, he kills her, beheading her with an ice skate, the emblem of his profession. It is not safe to sleep with patriarchy.

The movie concludes with two powerful gestures of affirmation and forgiveness.

We see Milena’s disembodied head on an autopsy tray. As the camera zooms in past the forensic investigators, her head comes to life and addresses us, describing the outcome of her liaison with Vladimir Ilich, “a genuine Red Fascist.”

“Comrades!” she proclaims, indomitable even in death. “Even now I am not ashamed of my communist past.”

This is Milena speaking for Wilhelm Reich, but it is also Makavejev speaking—and through him, it is Yugoslavia speaking, and the entire 20th century. Milena’s refusal to feel shame about her fate is Makavejev blessing humanity: all our clumsy efforts to free ourselves, all the revolutions and liberation struggles that ended in dictatorship and dogma, all our human frailty. There is nothing in this human world of ours that is not in some way right, however distorted it may be.

Then the camera cuts to Vladimir Ilich, her murderer. Utterly bereft, he is staggering through the snow, his hands soaked in blood, recoiling in horror from himself. Imagine if all the dictators, mercenaries, and rapists in the history of the world suddenly came to understand all the harm they have done, experiencing in full the tragedy they have inflicted.

Makavejev has Vladimir Ilich sing “François Villon’s Prayer” by Russian singer Bulat Okudzhava, whose recordings were suppressed in Russia at the time:

Before the earth stops turning

Before the lights go dim

To each one, Lord, I pray thee

Grant what is needful to him…To the one whose hand is open

Grant rest from charity

A gift of remorse to Caine

But also, remember me…Oh Lord, thou art all-knowing

I believe in Thy wisdom then

As the fallen soldier believes

That in heaven he’s alive again…As all men must believe

They know not what they do…

Grant to each some little thing

And remember, I’m here too.

“And remember, I’m here too,” entreats Vladimir Ilich, begging for an impossible absolution at the end of a century of holocausts. “Remember, I’m here too,” repeats Okudzhava, and we see Milena’s smile become Reich’s.

In giving remorse to Caine, Makavejev implores us to compassion—not just for Milena, Reich, himself, and all who have suffered at the hands of authoritarians, but also for Lenin, for Stalin, for Tito and Eisenhower, for all of humanity locked in cycles in which we do harm to those we love. This is Makavejev’s answer to the moral binaries of the partisan blockbuster.

Makavejev’s trialectics: Milena, protagonist of WR, both dead and alive, and director Dušan Makavejev himself.

Speaking about WR years later, Makavejev reflected:

You can die from freedom, like you can die from too much fresh air, if you are not used to it… I think that over-controlled people have very good reasons for saying that freedom is dangerous. When over-controlled people relieve their irrationalities, they often become chaotic, narcissistic, murderous, or suicidal because they just can’t stop.

This implies that the proper road to liberation is a carefully managed process in which the free expression and satisfaction of sexual desire can be properly moderated. In other words, repressive desublimination. But can you really die of too much fresh air?

As so often occurs, the tale is wiser than the teller. It’s not too much freedom that kills Milena and makes Vladimir Illich into a murderer. Radmilović, the representative of chaos and irrationality, does no harm to anyone, and almost succeeds in quarantining Vladimir Ilich. The problem is not too much freedom, but too much control, too much certainty, too much doctrine. The realization of any totalizing system brings all its flaws and fault lines into relief, magnifies them—like the USSR—to the size of continents.

The dismembered corpse of Yugoslavia in 2018.

We can read WR as a simple allegory of 20th-century international relations: smitten with the USSR, Yugoslavia throws herself at him, only to be betrayed. But if we read Vladimir Ilich more abstractly as a symbol of patriarchal nationalism, it appears that Makavejev foretold the civil war of the 1990s twenty years in advance.

Like Milena, Yugoslavia was murdered, torn apart by authoritarian currents that had never been rooted out by the sham self-management of state socialism. Just as no dictatorship can create the conditions for the liberation of humanity, in the final analysis there is no such thing as an anti-fascist state. The same seeds of fascism and civil war lurk within all nationalisms, within all valorizations of power and duty. Every nation will be a time bomb like Yugoslavia until we disassemble all of them down to their deepest foundations, which are rooted deep within ourselves.

Should we attribute Yugoslavia’s collapse to an excess of id or a surfeit of superego? Did the nationalist wars that tore up the country represent unfettered desire giving rise to violence, or were they caused by the forces that have always distorted and repressed desire? Was the problem too much freedom on the scale of the nation—or too much despotism on the molecular level, the scale of the individual?

How we answer these questions will determine how we respond to nationalist violence in the 21st century: whether we understand it as an excess interrupting the present order or as the purest manifestation of that order. Is desire itself the problem, to be controlled with laws and interventions from transnational military bodies? Or is control the problem, which we can only undermine from the bottom up by means of autonomous subversion and transgression? Is the solution a greater nationalism—Yugoslavian rather than Serbian and Croatian, for example—or to abolish all forms of nationalism once and for all?

And how can we set out to do that without replacing nationalism with another dogma, another ideology? Makavejev’s methodology and compassion give us a point of departure.

“Men [sic] fight and lose the battle, and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant, and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name.” -William Morris, A Dream of John Ball

Further Reading

- Jennifer Lynde Barker, The Aesthetics of Antifascist Film: Radical Projection

- Marc James Léger, “WR: Mysteries of the Organism Today”

- Dušan Makavejev, Poljubac za drugaricu parolu

- Lorraine Mortimer, Terror and Joy: The Films of Dušan Makavejev

- Richard Porton, “WR: Mysteries of the Organism: Anarchist Realism and Critical Quandaries”

-

Compounding the (faux) documentary aesthetic of WR, all the main characters with the exception of the Russian, Vladimir Ilich, are named for the actors who play them. “Excuse me,” Vladimir Ilich interjects at one point, “this is a photo montage, isn’t it?”

“No, it’s authentic,” answers Milena. ↩

-

In summer 1971, political figures and “cultural workers” attended a special screening of WR in Novi Sad in order to decide whether to ban it. Some 800 people attended. The screening was interrupted by both applause and booing; the atmosphere was electric during the subsequent discussion.

Many people supported the film. The critic Petar Volk defended the freedom to criticize, insisting that Makavejev shouldn’t be seen as “a typical anarchist, nor a typical artist, anti-artist, communist, anticommunist.” He insisted that every work of art is political, but that even when art criticizes, it shouldn’t be seen as hostile.

Most political figures spoke against WR. One said, “The film placed all of the ideologies of the world in the same hole, including the ideology of self-management. Some have tried to defend it here, saying that the struggle against every dogmatism shouldn’t accept any dogma. I agree with that. But we have to say where we are, on which side, for what ideology. Fascism and anti-fascism, Stalinism and anti-Stalinism do not go together…”

Another: “I think this is a real political diversion and an attack on things we consider holy, such as Lenin, such as a communist red flag, our movement, our efforts and the victims we sacrificed and still sacrifice for that. This is throwing mud on all of those holy things…” Still another said that if Petar Volk showed up among his workers with his long hair, they would throw him out head first.

Even after this debate, the Commission for Cinematography allowed the film, but the public prosecutor banned it the following month. The ban was lifted only in 1986. ↩

-

“I’ve been to the East, and I’ve been to the West, but it was never like this!” Vladimir Ilich says of Makavejev’s Yugoslavia. ↩

-

Kupferberg was an anarchist, a pacifist, and a member of the subversive New York City rock band, the Fugs. ↩

-

For a chilling example of how “non-statist micro-politics” of affective subversion can be reappropriated for the project of repression in the same way that revolutionary communism became the state religion of totalitarian nations, consult Eyal Weizman’s “Walking Through Walls,” in which he relates how the Israeli Defense Force employed concepts from A Thousand Plateaus by Deleuze and Guattari to strategize assaults on Palestinian refugee camps. ↩

-

“Every fury on earth has been absorbed in time, as art, or as religion, or as authority in one form or another. The deadliest blow the enemy of the human soul can strike is to do fury honor. Swift, Blake, Beethoven, Christ, Joyce, Kafka, name me a one who has not been thus castrated. Official acceptance is the one unmistakable symptom that salvation is beaten again, and is the one surest sign of fatal misunderstanding, and is the kiss of Judas.”

-James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, quoted in Myron Sharaf’s biography of Wilhelm Reich, Fury on Earth. Sharaf appears in WR in the documentary material. ↩

-

Beethoven’s 9th Symphony also figures prominently in Makavejev’s films Man Is Not a Bird and Sweet Movie. ↩